History of the Warsaw ghetto

WARSAW GHETTO 1940–1943

Before World War II, Poland was home to the largest Jewish community in Europe. Most Polish Jews, unlike the general population, lived in cities. Warsaw was the center of Jewish social, cultural, political and religious life. In 1939, on the brink of Nazi Germany’s invasion of Poland, nearly 370,000 people lived in the capital. Jews constituted just under 30 percent the city’s total population.

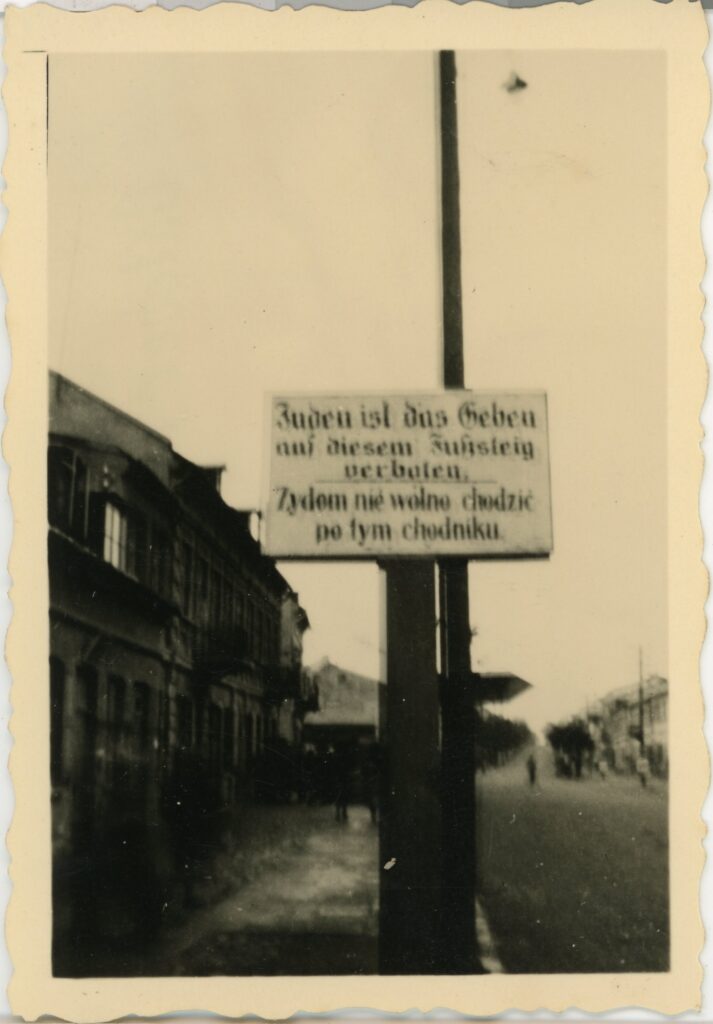

After the outbreak of World War II, restrictive, racist legislation was gradually introduced in the areas occupied by Germany. The obligation of forced labor was imposed on the Jews. Ritual slaughter was forbidden and synagogues were closed. From December 1939, Jews in the General Government were forced to wear an armband with the Star of David on their right forearm. Soon they were banned from using many public institutions, such as libraries, railways, and even parks. Restrictions on professional work were also introduced, including for doctors and lawyers. The process of displacing Jews from the lands annexed to the Reich and to the General Government was also started. Until October 1940, nearly 90,000 of them came to Warsaw.

Already in autumn, the Germans began to create closed ghettos for the Jewish population, officially called ‘Jewish residential districts’. In total, there were about 600 ghettos in Poland during the war. The first of them was established in October 1939 in Piotrków Trybunalski. In the spring of 1940, there were plans to establish a ghetto in Warsaw, initially in Praga. The official reason was to stop the typhus epidemic, which was supposedly spreading in parts of the city inhabited mainly by Jews. The implementation of these plans was preceded by the process of isolating the Jewish population from the rest of the city’s inhabitants. In March, Warsaw Jews were banned from entering ‘Aryan’ restaurants and cafes. With the consent and most probably inspired by the Germans, during the Easter holidays, between March 22 and 27, 1940, an anti-Jewish pogrom took place in Warsaw, which was to justify the creation of the ghetto. The majority of the participants of the pogrom were schoolchildren inspired by activists from the circles of the National Radical Organization.

In April 1940, on the order of the German authorities, institutions representing the Jewish community began erecting walls around the part of the city most populated by Jews, the so-called northern district (today’s Muranów), where a ghetto was to be established. The decision delineating its area was issued by the head of the Warsaw district of the General Government, Dr. Ludwig Fischer, October 2, 1940. As a result, 138,000 Jews and 113 thousand. Poles had to change their place of residence. The final closure of the ghetto in Warsaw took place on November 16, 1940. About 400,000 Jews were left behind the walls. In April 1941, when the displaced from the towns of the Warsaw District and a group of German Jews arrived in the ghetto, this number increased to 450,000 people. For leaving the designated area of residence, under the ordinance of the Governor General Hans Frank, issued on October 15, 1941, there was a death penalty. This also applied to those helping Jews outside the ghettos, on the ‘Aryan side’.

The Warsaw ghetto was theoretically managed by its own local government, the collegiate Jewish Council (Judenrat) established by the Germans in October 1939 to replace the former Jewish Community. It was led by Eng. Adam Czerniaków. In fact, the Judenrat operated under German supervision and was forced to comply with all the regulations of the occupation authorities. The great challenge was to organize the lives of nearly half a million people in conditions of enormous overpopulation and a lack of sources of income and food. From the beginning of the Warsaw ghetto, the main problems were: hunger, infectious diseases, poor sanitary conditions, slave labor and contributions imposed by the German authorities. Due to the tragic living conditions, the mortality rate increased dramatically. By July 1942, a total of 92,000 people had died in the ghetto. Nevertheless, in these inhumane conditions, attempts were made to lead a ‘normal’ life. There were – legal and illegal – charitable, educational, religious and cultural institutions. The political underground, issuing dozens of conspiratorial magazines, developed. From the spring of 1942, an armed underground began to form more and more actively, and the Antifascist Bloc was established. Its activity was paralyzed by the lack of a clear conception of combat and a lack of weapons, as well as the arrest of the commander of the organization, Pinkus Kartin (aka Andrzej Szmidt), on May 20, 1942.

After the launch of Operation Barbarossa by the Third Reich in June 1941 and the German successes on the Eastern Front, the implementation of the Nazi concept of the ‘Final Solution to the Jewish Question’ took the form of systematic murder. Jews were killed in mass executions, and then in specially created extermination centers. The first of these was established in December 1941 in Kulmhof (Chełmno on the Ner), in the Polish lands annexed to the Reich. The next ones were established in the General Government in Bełżec, Sobibór and Treblinka. In the spring of 1942, the Germans started the so-called Operation Reinhardt, the aim of which was to liquidate ghettos in the General Government and murder the Jews living there.

On July 22, 1942, the so-called Grossaktion (Great Liquidation Action), i.e. the deportation of local Jews to the extermination camp in Treblinka, began. In just two months – until September 21, 1942, when the last of the transports departed – nearly 300,000 people were killed there. Only 60,000 Jews remained in the area of the reduced ghetto. This was made up of people employed in enterprises producing for the Third Reich, or illegally living in the ghetto.

In the morning of April 19, 1943, when the Germans began the final liquidation of the ghetto and the next wave of deportations, they were fired upon by groups of the Jewish armed underground – the Jewish Combat Organization (ŻOB) and the Jewish Military Union (ŻZW). The first of these organizations consisted of members of various left-wing groups, while the second was mainly fought by representatives of the Zionist right. The heaviest fights took place in the vicinity of Muranowski Square, where the ŻZW headquarters was located, and in the area of Zamenhofa and Franciszkańska Streets, where ŻOB fought.

On May 8, 1943, the bunker at 18 Miła Street, in which the ŻOB command was hiding, was discovered by the Germans. Mordechaj Anielewicz, the commander of this organization, died then. This date can be considered the symbolic end of the ghetto uprising. For the Germans, the end came with the blowing up of the great synagogue in Tłomackie on May 16, 1943. Jürgen Stroop, who was in charge of the liquidation of the Warsaw ghetto, wrote in a report to Heinrich Himmler: “There is no longer a Jewish residential district in Warsaw.”

Some of the Jews who had stayed in the ghetto until this point were deported and murdered in Treblinka, while most of them were deported by the Germans to the Lublin region, where labor camps were established. They were murdered at the beginning of November 1943 during the so-called Operation ‘Harvest Festival’. Many Warsaw Jews sought shelter on the ‘Aryan side’. Most of those who survived the war managed to survive within the territory of the USSR.

dr August Grabski