Zofia Hertz – the bedrock of “Kultura”

She was one of the most important figures in the Polish post-war émigré community. Together with her husband Zygmunt Hertz and Jerzy Giedroyc, she ran the Literary Institute, which published the famous “Kultura” magazine in Paris. Giedroyc would later recall: “If it hadn’t been for Zofia, I wouldn’t have been able to make it…”

“She remained, for me, a somewhat mysterious person: to have such reserves of energy and dedication! If it was infatuation, if it could be explained by the feeling of love. However, I think it was rather a fascination with an idea. Understanding that Giedroyc was a remarkable man in his stubbornness, and that although he might lose as a man, he would leave behind a great work”. This is how the writer Czesław Miłosz described her. Others appreciated her common sense, strong will, realism and restraint in showing her feelings.

Zofia had a difficult childhood. She was born on 27 February 1910 in Warsaw, however, during the Second World War, her year of birth was changed to 1911. She came from an assimilated Jewish family. Her father was baptised in the Catholic Church. Zofia was the daughter of Ludwig Neuding and Helena (née Nisenson). The bride’s family opposed the marriage for a long time, as did the sisters of Zofia’s fiancé, since he was widely (and rightly so) regarded as an irresponsible, careless man. After the wedding, the newlyweds left for Vilnius, where their son was born. The boy, however, soon died of croup. The couple divorced after four years of marriage. At the end of her life, Zofia recalled with regret that she had never seen her parents together…

Helena and little Zofia returned to Warsaw, where they moved in with Helena’s mother. She got a job as a clerk. Although Helena was irregularly paid modest alimony by her ex-husband, she actually received more financial help from his family than from him. Helena died of pneumonia when Zofia was eight years old. Zofia’s father had no interest in his daughter. The journalist Elżbieta Sawicka recalled that when young Zofia went to see her father, who had already married another woman, he denied she was his daughter and pretended to be her uncle.

After her mother’s death, Zofia lived with her aunt in Łódź, but later had to manage on her own at a boarding school. She passed her final exams (matura) at the Konopczyńska-Sobolewska Female Gymnasium. Her student’s report card reads: “intelligent, talented, very lively, although inattentive” and “suffering from eye disease” (which she struggled with for the rest of her life). During her school years, she made a living by working as a tutor, which she extremely disliked.

She dreamt of studying medicine, but it was too expensive for her and additionally, it would make it impossible for her to earn extra money. She decided to study law instead, while at the same time taking up employment in a law firm. Her boss, Apolinary Karnawalski, a notary public in Łódź, persuaded her to take the notary exam. Her first application was rejected, probably due to the fact that she was a woman. However, she tried again, and on 13 May 1933, she passed the exam with flying colours, becoming the first female notary public in Poland. Even local newspapers in Łódź gave her credit for her achievement. However, due to the legislation at the time, she could only work as a notary clerk until the outbreak of the Second World War.

In 1938, she met her future husband at a ball. Zygmunt Hertz was two years older than her and came from a wealthy Jewish family. As she recalled, “I started dating him out of spite. I was annoyed by his pretentious attitude and decided to cure him of it, which I succeeded in doing, by the way”. He studied economics in England and worked in his father’s business office. They married in February 1939. When the war broke out in September 1939, Zygmunt was enlisted as a reserve second lieutenant. The couple reunited in Stanisławów in 1940 and then made their way to Lviv, from where they were exiled to Tsinglok in the Mari Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. “The journey took almost a week, we were given salted herrings to eat, and the heat was unbearable”. There, they worked hard for 16 months clearing the forest. Zofia could hardly hold the heavy axe. They lived in a barracks full of bugs. Their daily food ration was two slices of bread for a whole day of hard physical work. In order not to die of starvation, they sold the clothes they had taken with them. The couple regained their freedom under the Sikorski–Mayski agreement and became soldiers in General Władysław Anders’ Army.

Zofia was in charge of propaganda in the Department of Culture and Press at the Army Headquarters, in the Propaganda and Education Office. Her manager was Józef Czapski, who barely survived imprisonment in a Soviet camp in Starobelsk. Zygmunt served in an artillery regiment throughout the Italian campaign, including the famous Battle of Monte Cassino.

During her wartime travels, Zofia met Jerzy Giedroyc in the Middle East in 1943, whom she described as a “very handsome but terribly grumpy man”. Although they did not take a liking to each other at first, the relationship turned into a 60-year long friendship, during which time Giedroyc referred to Zofia as “Darling”. They exchanged as many as 420 letters, which are currently being compiled.

We do not know how Zofia really felt about Giedroyc, although it was rumoured that she had put her only marriage at risk several times for the man. Jerzy Giedroyc came from a collateral line of a Lithuanian princely family. His father was a pharmacist. Jerzy studied at a school in Moscow, where he witnessed the February Revolution of 1917. He later returned to Poland, where, in 1931, he married a beautiful Russian woman, Tatiana Shevtsova, probably of Jewish descent. They separated before the Second World War and officially divorced in 1947.

The famous “Kultura” magazine was established on 11 February 1946 in Rome for demobilised Polish soldiers who had served in Anders’ army. Initially, the magazine was funded by a loan from the Soldiers’ Fund. In its first year, as many as 28 issues were published.

The magazine became even more popular after it changed its headquarters to the town of Maisons-Laffitte on the Seine, 18 kilometres from Paris, based on General Władysław Anders’ consent granted in August 1947. The official explanation for the relocation was the shorter distance from the new headquarters to Poland. In reality, however, the creators of “Kultura” did not share Anders’ belief in the rapid outbreak of the Third World War, which was to free Poland from Communist rule. That is why they did not settle in London, which was the main political centre of Polish post-war emigration.

Zofia and Zygmunt decided not to return to communist Poland. Besides, she wanted to continue her cooperation with Czapski and Giedroyc. She was interested in editorial work and later recalled: “My husband sacrificed his life and career for me. But I could not imagine how it would all work out in the end. I had to do something. We were thrown into deep water without being able to go back home”. For the first few years, they were boycotted by the French literary community, which considered “Kultura” to be a base for American spies. This was a false accusation, as Giedroyc was very concerned about highlighting the independent nature of his publishing house. At first, the creators of “Kultura” settled down in the French headquarters of the 2nd Anders Corps post. They became independent as early as mid-June 1949. Jerzy Giedroyc wrote to the writer Andrzej Bobkowski: “Having sent a letter of gratitude for the help received so far, I have put up the black flag of anarchy and independence”.

The famous Parisian “Kultura” printed Polish literary and journalistic works that could not be published in the People’s Republic of Poland for censorship reasons. They appeared in the monthly magazine, of which 637 issues were published. From 1953 onwards, the publications were released as separate books in the series “Biblioteka Kultury”, which numbered 511 publications. “Zeszyty Historyczne” was, in turn, devoted to the recent history of Poland and its immediate neighbours.

Without exaggeration one can claim that if it had not been for “Kultura”, the 20th-century Polish literature could not have boasted such masterpieces as: “Dziennik” by Witold Gombrowicz, “Dziennik pisany nocą” by Gustaw Herling-Grudziński, essays by Jerzy Stempowski and Józef Czapski, as well as numerous works by Czesław Miłosz.

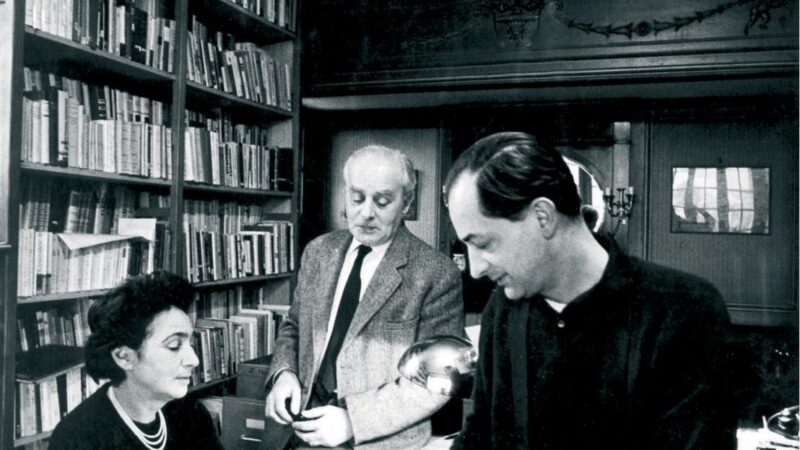

The breakdown of tasks was clear. Jerzy Giedroyc was the founder and editor of the magazine. Zofia Hertz, with her organisational skills, was in charge of administration and translation. The team also included: Zygmunt Hertz, Józef Czapski and Giedroyc’s brother Henryk.

By design, “Kultura” was not associated with any particular Polish political grouping in exile. Giedroyc defined the main task of his magazine in the following way: “It will usher in a process of thought which must eventually lead to the arrangement of Polish life on the principles of political equality, social justice and respect for human rights and dignity. Times are coming when the books offered by the Literary Institute in this section will have to be known not only by every political and social activist, but by every contemporary, cultured Pole”.

The basic principle of “Kultura” was its political independence closely linked to financial independence. In 1954, the founders managed to buy their own house with funds from friends and loyal readers.

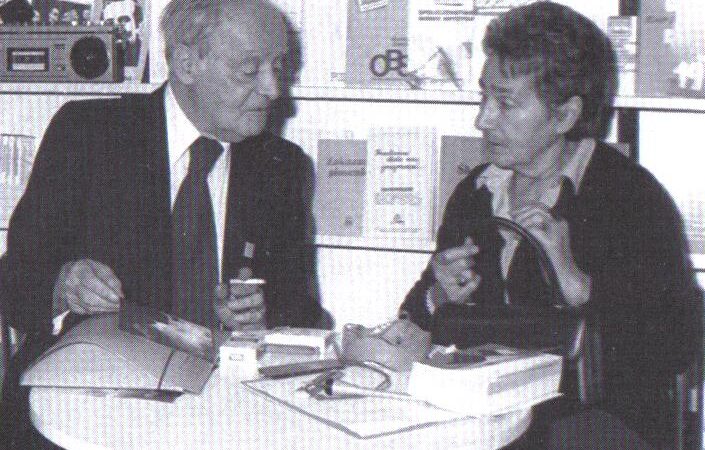

After Stalin’s death and the political thaw, the headquarters of “Kultura” became a very important place on the map for the Polish intelligentsia. They were visited several times by the writer Aleksander Wat and his wife, who had been in France on a Ford Foundation scholarship since 1957. Wat described Zygmunt Hertz as “a lovely man, extremely helpful and resourceful, full of love for fellow brethren”. In 1961 and 1962, the Wat couple lived for two months in the house. However, in the following year, the first disagreements arose. These were related to politics, but also annoying petty requests, like, for example, Ms Wat persistently demanding an extra blanket for her husband during a festive dinner. Wat would later recall: “The penny-pinching Zofia and Zygmunt regarded us as self-interested, greedy and ungrateful people. The gift for Zosia’s name-day was bought in the most expensive shop chosen by Zygmunt, the restaurants, the spending – all for show. I am criticising the Hertzs, although we do believe that Zofia is a reliable, although not a very good person, while Zygmunt is a really good-hearted, though greedy man”.

“Kultura” was also home to the youngest generation of Polish artists. In the summer of 1957, a group of friends from the Student Satirical Theatre went to Burgundy for the wine harvest. Agnieszka Osiecka came to the Hertz couple to personally hand them the typescript of Marek Hłasko’s “Cemeteries”. She recalled: “The grey villa smelled of perfume and pipe, a black spaniel guarded the house and everyone was still alive at the time. Józio Czapski lived upstairs, while the space downstairs was shared by three people I was to get to know and love for my entire life: Giedroyc with his hermit-like demeanour, Zygmunt Hertz, a kind and talkative spirit, and – as Miłosz described her – the amazing Zofia, the pillar of the house and the publishing business. Jerzy Giedroyc had an extremely strong spiritual influence on me. He rearranged things in my head, changed my horizons – it was like brain surgery”.

The Hertz couple became parental figures to the young poet. The 50-year-old Jerzy Giedroyc, as it turned out years later, fell in love with the young Agnieszka Osiecka – most likely with reciprocity. He would fondly call her Kikimora and visit her in London, where she was staying with her aunt. “I would stare at him shamelessly, enthralled. Someone could have said that we met in the wrong place at the wrong time. But if we had met somewhere else and at another time, I don’t know if it would have been as important and serious – as it is now”.

Unfortunately, in the following years, the visit came to an end after Osiecka had her passport seized by the Polish Security Service. Another member of the Student Satirical Theatre, Jarosław Abramov-Newerly, replaced Osiecka as the Hertzs’ “foster child”. One of the guests of “Kultura” was Marek Hłasko, who visited it twice, in 1958 and 1965. Hłasko, especially after his second stay, was described as: “an unbearable man, doing things in spite of himself, wasting every opportunity that comes along his way, a psychopath, mythomaniac, hypochondriac, and god knows what else. Impossible to deal with. The strangest thing about him is his popularity with women. That’s what I don’t understand, as he’s a neurasthenic, dirty slob to the point of smelling foul, a drunkard and troublemaker at times.”

Zofia Hertz was secretary of the Literary Institute. She dealt with legal and financial matters and correspondence, and was a person who, in Irena Vincenz’s words, “held everything in place”. Zofia was also an editor of manuscripts and, as Miłosz called her, “an executioner of stylistic errors”. In addition, she translated texts from French and Italian, and ran a regular column, “National Humour”, for almost a quarter of a century. She recalled: “Jerzy was the brains and conceptualiser of the whole undertaking. He was not afraid to take risks and had great ideas. He was very intelligent, well-read, and was the one who created that special atmosphere surrounding “Kultura”. As for myself, I knew how to bring them all together and how to mitigate conflicts, regardless of their different personalities. I was also in charge of all the practical aspects of our activity. Wacław A. Zbyszewski wrote: “It is incredible how Zofia manages to do the proofreading, the accounts, the finances and correspondence, supervise the printing process, fold the issues, keep an eye on the editing, shipment, and, while doing all that, still find time to welcome guests and cook for the whole group – all the time looking fresh, youthful, elegant and chic. Zofia Hertz is the one to decide who to admit to the lodge or, more often, who to expel from the circle of fidèles”.

Giedroyc loved her common sense, which kept him from getting involved in risky matters. Zofia’s biographer, Kamila Łabno-Hajduk was moved by the diligence of Hertz and her friends: “All the work on the texts was done by hand. Zofia often had to type manuscripts first and only then work on the text. Typesetting and proofreading were also done manually. They really did not seem to have a private life; there was no time for that. Their dedication was limitless”. Zygmunt Hertz passed away in 1979, Maria Czapska in 1981, and her painter brother, Józef Czapski, in 1993. Jerzy Giedroyc passed away in 2000. Zofia took over the management of the Literary Institute. In October 2000, as instructed by Giedroyc, she published the last issue of “Kultura” in Paris. The Literary Institute became an archive and a library. As she herself wrote: “Don’t wait for me to retire. I am the type who dies while on duty”.

She passed away on 20 June 2003 in Maisons-Laffitte. She is buried in the nearby cemetery, Le Mesnil-le-Roi, where all the founders of the Literary Institute – Zygmunt Hertz, Maria Czapska, Józef Czapski and Jerzy Giedroyc – are buried. “It was our life. We worked round the clock, with no time off. There are few people who would be prepared to do that. We devoted our lives to “Kultura”, because we did not have much of our own”.

Agata Olenderek