We Have to Live in the Moment and Do Our Part

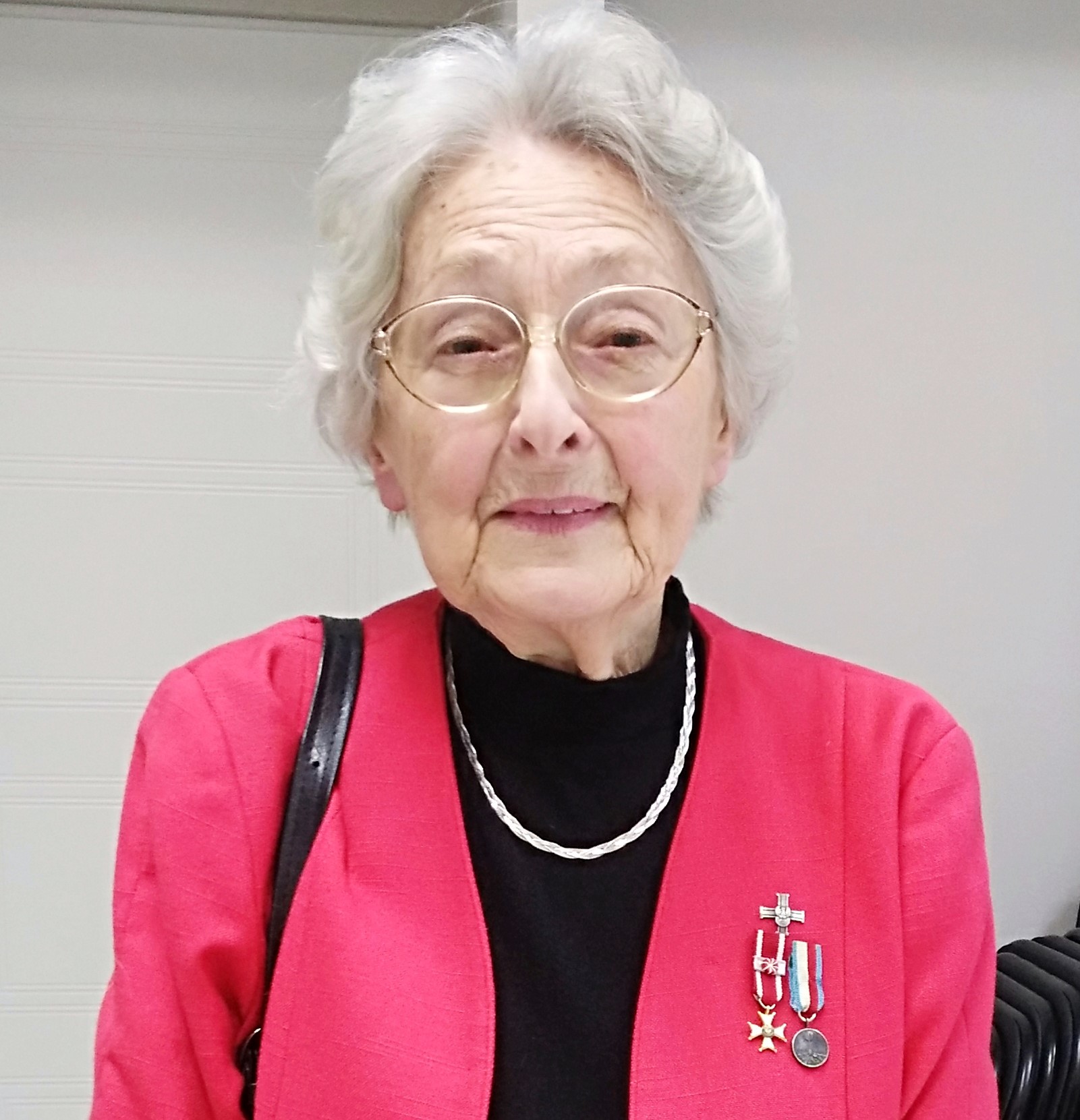

On 6 March, we celebrate the European Day of Remembrance for the Righteous, established by the European Parliament in 2012 on the initiative of the Gardens of the Righteous Worldwide Committee (GARIWO). On this occasion, we talked with Anna Stupnicka-Bando – the President of the Polish Association of the Righteous Among the Nations – who is a member of the Gardens of the Righteous Committee.

Anna Stupnicka-Bando and her mother were honoured with the title of Righteous Among the Nations by the Yad Vashem Institute on 19 September 1984. During the occupation, they hid Liliana Alter – a daughter of a Bund activist, who was extracted from the ghetto, Hilary Alter, a boy Ryszard Grynberg and Mikołaj Borenstein. After the outbreak of the Warsaw Uprising, Anna Stupnicka, who was 15 years old at the time, served as a medical orderly in the Sub-district II of Żoliborz of the Home Army (AK). After the war, she worked as a neurologist.

How important is it in today’s word to award people for their resistance against genocide, helping the victims of war and ethnic cleanses, defending freedom in totalitarian regimes? These are the attitudes noticed and noted by the Garden of the Righteous Committee…

Today is a very important day because we cannot forget about people who do something for others, sacrifice themselves, stand up to regimes and any activities aimed at the destruction of the good. This day should be celebrated all around the world, for everyone to remember that the good must prevail. Not fraud, not lies, but good above all. Not everyone believes in it, and that is why, we need to uphold the faith in the good at all cost. People who survived the war knew what it meant to sacrifice for someone, or something. Today’s Righteous sacrifice in the name of an idea, to fight evil in many of its forms.

Together with your mom, Janina Stupnicka, you saved three Polish Jews during the occupation. Did your mom – as far as you remember – hesitate, even slightly, before taking Liliana Alter out from the Warsaw Ghetto?

No, she did not hesitate at all. She was a very brave woman all of her life. She did not listen to anyone, even her family – sisters and brothers – who opposed when mother would take me to the Warsaw Ghetto to bring a loaf of bread and some beetroot jam in my school briefcase. Mom did not pay attention to what they said and believed that a piece of bread may, if not save, then at least somewhat extend a life in the horrible conditions of the ghetto. She set her eyes on a very poor family with seven children, who lived in extreme poverty.

Did your mother know the family before the war? Or maybe she got to know them in the ghetto, where she used to go with registration books?

No, she did not previously know them. Maybe they were called Śledź, but I am not sure. This rare surname stuck in my head. I don’t know what happened to them later.

Did your mother know Liliana’s father, Hilary Alter, before the war?

No, they didn’t know each other. I don’t know how they met in the ghetto. Hilary Alter was a very brave man. He left Liliana with us, and his wife was placed somewhere near Warsaw. He was a blue-eyed, blonde man with a very Slavic appearance. He had documents that allowed him to join the partisans, the People’s Army (AL) – he had a cousin in the woods. But he didn’t want to. He was a member of Bund and thought that he might be needed in the ghetto. My mother didn’t know Alter or Grynberg family before the war, nor doctor Borenstein, who lived in Łódź. I have never talked about it before, but we also had a Jewish lady visit us every day. She taught us French, German, and the piano. She was a very nice, cultivated lady, née Koral, she married a Pole – Barliński. Her grandson, Krzyś, became a doctor, but I don’t know if he stayed in Poland. Miss Janina – who didn’t have Semitic features either – taught me a little bit of German, and talked with my mother in French. She visited us everyday at 25 Mickiewicza Street in Żoliborz to warm up her supper. She received food from the Central Welfare Council and brought it to our house. I remember the smell of these, as Ms. Janina used to called them, “croquettes” up until this day. During the uprising, she had typhus. She lived at Słowackiego or Marymoncka Street. After the uprising, we completely lost touch.

You are involved in veteran affairs in the “Wawer” circle, you meet with young people – what do they think about the difficult, wartime choices, when you talk with them?

Today, young people are used to watching gruesome scenes in the movies. I talk to teenagers, the girls get a little touched. But I have to say that it is Jewish youth who is most interested in my stories. I meet thousands of young Israelis. One group can be as big as four hundred people. They always really listen. When I am talking about rescuing Jews, the boys cry and hug each other. Boys twice my size hug me with tears running down their cheeks. They respond much more emotionally than our youth. And I have to say that it really irritates me when people who do not know war at all and have not lived through it, say what should and should not have been done. They have no idea about the choices people faced. After all, each time you left home, you never knew if you are going to return in the evening. This taught me that you can never be sure of anything in life. That is why, we have to live in the moment and do our part.

Interview by: Anna Kilian