“The ashes from the ruins rose high and far.” – Liberation of Auschwitz

27 January 1945 is a symbolic date for the former prisoners of the Auschwitz camp complex. In the afternoon, soldiers of the 60th Army of the First Ukrainian Front opened the gates of the camp, which had been abandoned by the Germans. When they entered, there was silence; a few prisoners were hiding in the barracks. The Germans, knowing the situation at the front and following the Red Army offensive, had had time to prepare the evacuation, so the vast majority of the living prisoners had been taken out of the camp in the days and weeks before. The weakest and sickest inmates and the children were left behind.

The emptying camp

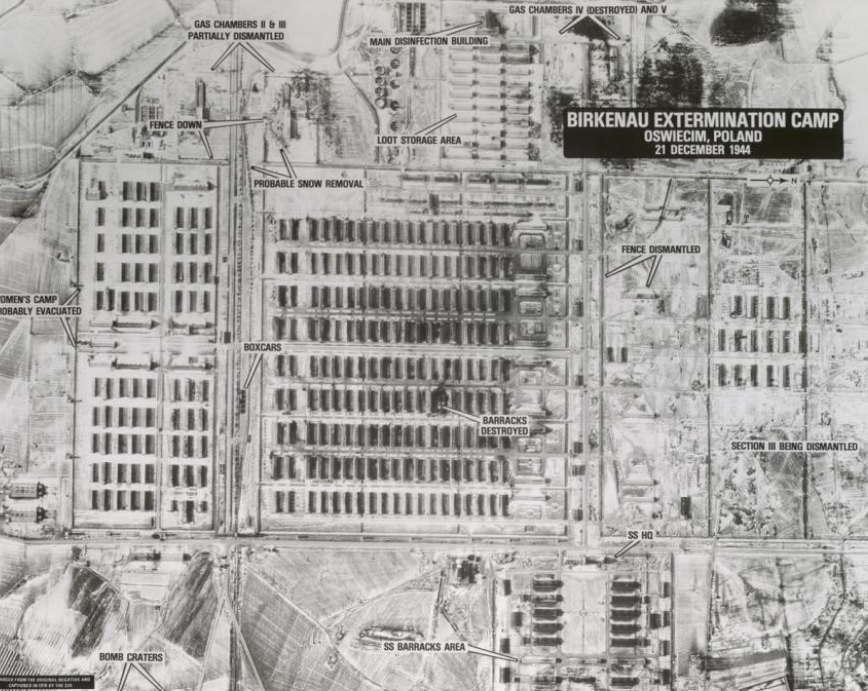

On 21 December 1944, a reconnaissance plane appeared in the sky above the German Nazi Auschwitz concentration and extermination camp. The pilot was meant to photograph the I. G. Farben facilities where fuel and synthetic rubber were produced. His task was to document the damage caused by previous air raids, the air defence installations and any signs of expansion of the plant. The photos were quickly developed and used to plan the air raid on the industrial plant, after which they were archived for years. It was not until the end of the 1970s that CIA employee Dino A. Brugioni took a closer look at the shots from this reconnaissance mission. As it turned out, in addition to the industrial plants, the pilot accidentally captured some unique images of the Auschwitz II Birkenau camp being demolished.

In the fall of 1944, the prisoners of the German Nazi Auschwitz concentration and extermination camp sensed the coming changes. Successive transports of people were leaving the camp for concentration and labour camps within the Reich, as far away from the front line as possible. Seweryna Szmaglewska, a prisoner of Auschwitz II Birkenau and a well-known writer after the war, recalled the emptying camp: ‘The camp fell silent, as if it had died. Towards evening, a prisoner from the men’s camp comes to the registration office on business. He is very depressed. […] When asked about the news, he quietly says: “Well, we’re leaving.” […] The Poles from Birkenau did not go to work today either. After all, you don’t see any columns of men anywhere. After the roll call, they will go to the former gypsy camp. They will be awaiting transportation there’. For prisoners used to cramped conditions, noise, movement and constant haste, such changes must have been evident. In the second half of 1944, around 65,000 prisoners were deported from the entire Auschwitz camp complex. Most of them were Poles, Czechs and citizens of the USSR. Soon after the first deportations, the dismantling of the empty barracks began, initially in section III (visible on the right-hand side of the photo). Other buildings stood empty and unheated, as shown by the snow on their roofs.

At the end of November, the Germans murdered most of the remaining Sonderkommando prisoners. One of them, Leib Langfus, wrote notes that end: ‘We are now going to the zone. The 170 remaining men. We are sure they are leading us to our deaths. They have chosen thirty people to remain in Crematorium V. Today is 26 November 1944’. One member of the group, Filip Müller, described the selection in more detail. The remaining members of the Sonderkommando were divided into three groups. Thirty people were barracked at Crematorium V, several dozen people were assigned to join the prisoners working on the demolition of the crematoriums and gas chambers, and about 100 people were separated. Müller recalled: ‘We never found out what happened to them, but it was clear to us that their time had come’. Crematorium V remained in operation until the last days before the Red Army entered the camp, and the gas chamber was used for the last time on 28 November 1944.

Aerial photograph of Auschwitz II-Birkenau camp from December 21, 1944 | Yad Vashem Archives

Prisoners pass through the gate of KL Auschwitz | source: public domain

Filip Müller | source: public domain

‘Death marches’

In January 1945, in response to the Soviet army approaching the city, the German authorities decided to evacuate the camp. In Auschwitz on 17 January, after the roll call, during which 67,012 prisoners were reported, they were led out of the camp on foot, heading west. In total, around 56,000 prisoners were sent out from all Auschwitz sub-camps between 17 and 21 January. Exhausted from their stay in the camp, often without shoes, warm clothing or food, they set off in columns.

They were forced to march for long periods in the snow and bitter cold. Any attempt to move away from the column was severely punished. Most of them were sent to the train station in Wodzisław Śląski, about sixty kilometres away, where they were loaded into open freight cars and transported to concentration camps deep in the Reich. This part of the evacuation became known as the ‘death marches’ because the emaciated prisoners perished during many hours of struggling in the cold, or were murdered by their German escorts for slowing down the march or attempting to escape. After they left, there were about 9,000 prisoners left in the camp – most of them sick or extremely exhausted, and considered unfit to continue the journey.

At the same time, the camp was a frenzy of activity, as files were burned in the camp registry office. Szmaglewska, who worked there, recalled drawers full of death certificates and files with the names of the executed being taken away to be burned. Krystyna Żywulska, a prisoner evacuated in January 1945, recalled: ‘Piles of papers are burning in all parts of the camp. In front of the block leader’s office, the SS men trample on the burning piles, throw in new documents and letters of the deceased, destroying everything that could prove the truth’. Despite the chaos and the haste, the Germans tried to destroy the evidence of their crimes. They burned camp documents, films, and photographs of prisoners. Wilhelm Brasse, a prisoner and camp photographer, and Bronisław Jureczek threw too many photos and negatives into the furnace. In doing so, they blocked the smoke outlet and made the destruction more difficult; around 40,000 identification photographs of prisoners were saved. In retreating, the Germans also set fire to the ‘Canada’ barracks, where the victims’ belongings were collected. However, they did not manage to destroy all the clothes and objects inside.

Some materials were taken with the prisoners when they were led away. Some documents survived because the prisoners took advantage of the chaos and hid files that were intended to be burned. On 20 January, the partially dismantled Crematoria II and III and the adjacent gas chambers were blown up, and on 26 January, Crematorium V was destroyed. ‘Auschwitz was liquidated before its liberation’, Szmaglewska wrote in the summer of 1945.

Liberated prisoners, Auschwitz, Poland, 1945 | Yad Vashem Archives

A camp with no supervision

For the several thousand prisoners remaining in Auschwitz, this began a unique period where the norms and patterns by which the camp had functioned for years collapsed. After the prisoners were taken from Auschwitz, the guards stopped patrolling the area and the prisoners were left to fend for themselves. One survivor, Jakub Gordon, testified: ‘For almost a week, we were completely alone in the camp without any supervision’, and his fellow prisoner from the camp hospital elaborated: ‘There was a period of time when there was no German guard. […] Occasionally, a German soldier could be seen’. Shortly after the war, Primo Levi, an Italian Jew who was a prisoner in the Auschwitz III Monowitz subcamp and had been hospitalized with scarlet fever, wrote down his memories of the last ten days of the camp’s existence. He emphasized: ‘On the night of the evacuation [17/18 January 1945 – MG], the camp kitchens were still in operation, and the last soup was distributed in the sickbay the following morning. The central heating system was not being operated […] and the temperature dropped with every hour’. In the morning, bread was distributed for the last time and an SS officer made a tour of the barracks. In the evening, the last Germans left the sub-camp, and during the night some of the empty barracks were hit by air raids and burned down. The next morning, Levi and two companions went in search of a stove to heat the barracks and make food. The sight when they left the barracks took them by surprise: ‘What we saw was unlike anything I had ever seen or heard of in my life. The lager had barely stopped living and was already decomposing. Nowhere was there water or light; door and window hinges were torn off and fluttered in the wind […] ash from the ruins rose far and wide. The bombs wrought destruction and then people continued their work, ragged, emaciated, skeletal, sick, […] wandering everywhere. Chaos spread in the camp. Prisoners searched and vandalized rooms that had been off limits to ordinary prisoners, such as the camp kitchen and the rooms of the prisoner functionaries. Many cleaning tasks, such as emptying the latrines, were not carried out, and the camp was ‘unspeakably dirty’. It should be emphasised that this observation was made by a former prisoner, who was well aware of the unspeakable hygiene in the overcrowded camp before its evacuation.

However, this chaos did not mean total anarchy. Levi recalled a breakthrough moment when other patients decided to give him and his companions a piece of bread after he set up a stove to warm their common room. He wrote: ‘Until the previous day, something like this would have been unthinkable. The camp rule was: “Eat your own bread, and if you can, your neighbour’s bread too”, and gratitude was not allowed. So this was proof positive the camp had ceased to exist. This was the first human instinct in our community. I think it was the moment when we living beings began the slow process of transforming from prisoners back into people. The following days brought more instances of human behaviour. In the barracks, the prisoners tried to organise themselves to get food for their group, find firewood, maintain relative order, or otherwise improve their living conditions. The various groups also engaged in a lively barter with goods that they had managed to obtain in the camp or outside its bounds, even going into the camp guards’ abandoned quarters. On 21 January, prisoners from the main camp arrived in Birkenau with information about the food supplies stored in the SS warehouses, which were immediately looted. Other prisoners discovered piles of potatoes. The food they found there was enough to feed even the seriously ill prisoners who were unable to scavenge themselves. Despite these signs of solidarity, the conditions in the camp were still terrible and the food the prisoners found was not enough to restore their exhausted bodies.

Silence and howling wind

On a cold, windy Saturday morning on 27 January 1945, soldiers from the 100th Lviv Rifle Division patrol, part of the 1st Ukrainian Front of the Red Army, entered Auschwitz III Monowitz. The camp seemed deserted. The wind swept snow clouds, which only added to the desolate impression. It was only in the hospital barracks that they came across a group of prisoners, the others were hiding, unsure of who was entering the complex. That same afternoon, Red Army soldiers found themselves in the area around Auschwitz I and Auschwitz II Birkenau. They clashed with a group of retreating Germans. Both sides suffered losses, but the Germans were ultimately driven off. Around 3:00 p.m., the first Red Army soldiers entered Auschwitz I. As in Monowitz, they had the impression of entering a completely abandoned place. The prisoners were either too weak to leave the barracks or too scared that the Germans would return and their temporary freedom would be taken from them.

Primo Levi recalled the first Soviet patrol – four horsemen who ‘stood next to the barbed wire fence and began to look around, exchanging short, quiet words. With some strange embarrassment, they looked at the decomposing corpses, the scattered barracks and us, the few survivors.’ They were seen as the four mythical horsemen of the Apocalypse, not knowing exactly what they brought along. Did they really hold freedom? Primo Levi recalled that, over time, the dominant feeling, alongside joy, was deadly fatigue caused by the sudden release of tension and the need to process the camp experiences. As he explained, because of this fatigue, ‘only a few ran to greet the liberators, a few indulged in prayer’.

Both in the main camp and in the other parts of the complex, the prisoners lived alongside the seriously ill, the dying and the deceased. When the Red Army entered Birkenau, they found around 5,800 prisoners and around 600 bodies of those who had died or were murdered in the last days of the camp. The situation in the Monowitz sub-camp was even worse. According to Danuta Czech, one quarter of the 850 prisoners who remained in the camp after the evacuation died before the liberation. According to camp doctor Dr. Otto Wolken, about 7,600 people survived in the camp complex until the Red Army arrived. The bodies of the deceased were collected in Block 11 of the main camp and several pits dug in Auschwitz II Birkenau. At the end of February 1945, they were ceremonialy buried in mass graves near the main camp.

Timely assistance

In the following days, Soviet soldiers and Poles from Oświęcim entered the camp, cleaning it, caring for the sick and organising the camp area. Most of the former prisoners needed urgent medical attention. Those who felt strong enough were immediately released to go back home, while those in a serious condition, emaciated by hunger and disease, were detained in field hospitals set up in the camp and run by the military. One of these was operated in the main camp, in brick barracks, and the other in Birkenau. A Polish Red Cross hospital was also set up in early February. Everything found in the camp was used for emergency aid: clothes, blankets, even bunks. Starving people had to be restrained from eating excessive amounts of food. Over time, patients were transported from the other parts of the complex to Auschwitz I. As of March, all the patients were held in the main camp. It is estimated that more than 4,000 former prisoners required treatment. In May 1945, the hospital was visited by investigator Jan Sehn, who noted: ‘All the patients are malnourished and emaciated, most of them are bedridden’, he wrote, describing individual cases in more detail, including adult women weighing around 25 kg and measuring 155-60 cm in height, despite several months of medical care. Even in June, one or two former prisoners were dying in the hospital every week. In total, around five hundred people died after the liberation of the camp.

Survivors behind barbed wire fence after the liberation of the camp, Auschwitz, Poland, 1945 | Yad Vashem Archives

Gathering evidence

The first days and weeks after the end of the German occupation and the liberation of the camp were important in terms of gathering information on and evidence of the crimes committed there. The people who treated and cared for the former prisoners were the first to obtain information from them. During the process of cleaning up the camp, documents, photos and other objects that had been left behind or hidden were also found. At the same time, letters were sent to family members in various countries, detailing the fates of former prisoners, both survivors and deceased. Through the testimonies of the survivors and the analysis of the materials found at the camp, a picture gradually emerged of the crimes that had taken place.

The investigation was conducted by the Prosecutor’s Office of the First Ukrainian Front under the supervision of the Extraordinary State Commission of the Soviet Union for the Investigation of Crimes of the German Fascist Aggressors. Their task was, in part, to search the barracks and other buildings of the former camp. The extermination infrastructure was examined, including the remains of crematoria and pits where corpses were burned. In addition, the prisoners’ remaining belongings were secured. More than 340,000 items of men’s clothing and around 830,000 items of women’s clothing were found in the barracks of the former Canada camp. The discovery of huge amounts of human hair, weighing about seven tons, was particularly shocking. As a result of the public prosecutor’s actions, documents found in the former camp were sent to the Soviet Union for many years. Only a few months later, in May 1945, was the commission’s work published. It stated that four million people had died in the camp, but did not specify their nationalities or countries of origin. This figure was repeated for many years in official documents, education and commemorations. It was only work in the 1980s by French researcher and former camp prisoner Georges Wellers, and its subsequent refinement by Franz Piper, that verified these findings. These researchers used deportation data to reconstruct the number of victims, determining where the transports to Auschwitz departed from and how many people were on board. It is now accepted that approximately 1.1 million people died in the camp complex, about 90% of whom were Jews.

The Polish Commission for the Investigation of German Fascist Crimes in Auschwitz and, later, the Krakow branch of the Main Commission for the Investigation of German Crimes, conducted separate investigations. It was partly the work of its members that determined the prisoners were gassed with hydrogen cyanide, which was part of Cyclone B. The members of the commission also took a series of photographs, documenting the remains of the camp infrastructure. The materials collected during the work on site and the testimonies of former prisoners and witnesses were later used in the trials held before the Supreme National Tribunal, established in February 1946. The most famous of these were the trials of Auschwitz commander Rudolf Höss in Warsaw in 1947, and of forty members of the camp staff, which took place in Krakow the same year.

Robbery and commemoration

In the first months and years, the camp area was gradually demolished. Two transit camps for German prisoners of war were set up in the Soviet-controlled area. Both were shut down by the beginning of 1946. Soviet soldiers used available materials for their construction, thus changing the appearance and layout of the barracks. In addition, sometimes the area around the crematoria and incineration pits were dug up in search of valuables. Some movable property was packed up and taken to the Soviet Union.

The local population also contributed to the devastation of the camp area. When the inhabitants of the nearby villages returned to their farms, they needed materials to rebuild their houses. Wood from the barracks was used for this purpose. More useful or valuable items were also taken. Some people came to the complex in search of valuables, plundering the burial sites of bodies or their remains.

From 1945–46, the Soviet authorities gradually handed the camp grounds over to the Polish side. They were initially placed under the care of the Provincial Department of the Provisional State Authority. During this time, an inventory of the buildings was carried out. In early 1946, they were placed at the disposal of the Ministry of Reconstruction and the Ministry of National Defence. During this time, the barracks were partially demolished, but the demolition was halted in mid-1946, when it was decided a museum should be established at the site and that some barracks should be preserved as exhibits. At the beginning of the following year, an exhibition design was presented, by which the camp grounds were meant to serve as a ‘historical document’ and a testimony to Nazi crimes. On the seventh anniversary of the first transport of Polish prisoners to Auschwitz, on June 14, 1947, the exhibition opened on the camp grounds. This marked the beginning of the long-running process of transforming the area into a memorial site.

dr Martyna Grądzka-Rejak

dr Michał Grochowski

Bibliography:

- Archiwum IPN, Akta sprawy karnej w sprawie Rudolfa Hössa (AIPN, GK, 196)

a) Protokół wizyty w szpitalu, Jan Sehn

b) Zeznanie dr Otto Wolkena

c) Zeznanie Jakuba Gordona

d) Zeznanie Jakuba Wolmana

e) Zeznanie Luigi Ferri

- Bartosik Igor, Bunt Sonderkommando 7 października 1944 roku, Oświęcim 2015

- Brugioni Dino A., Poirer Robert G., The Holocaust Revisited: A Retrospective Analysis of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Extermination Complex, “Studies in Intelligence” vol 44, issue 4, 1978

- Czech Danuta, Kalendarz wydarzeń w KL Auschwitz, Oświęcim 1982

- Lachendro Jacek, Auschwitz po wyzwoleniu, Oświęcim 2015

- Levi Primo, Czy to jest człowiek; Rozejm; Pogrążeni i ocaleni, Wołowiec 2024

- Müller Filip, Eyewitness Auschwitz: three years in the gas chambers, New York 1979

- Szmaglewska Seweryna, Dymy nad Birkenau, Warszawa 1972

- Żywulska Krystyna, Przeżyłam Oświęcim, Warszawa 2011.