Rachel Zilberberg “Sarenka” (1920–1943)

Activist of Ha-Shomer Ha-Tzair, member of the Jewish resistance, fighter in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising.

In 2012, in Israel, writer and artist Ofer Aloni discovered an old World War II-era tin box in the attic of his family home after his mother’s death. Inside were letters written in Polish and old photographs related to his aunt’s wartime activities—documents that had not seen the light of day for 69 years. These materials shed new light on one of the heroines of the Jewish underground in the Warsaw Ghetto, previously scarcely mentioned in historical sources or studies. The woman in question was Rachel Zylberberg, known by her pseudonym “Sarenka” (“Little Doe”).

Rachel Zilberberg | Public domain

Rachel was born on January 1, 1920, into an Orthodox Jewish family of the Modrzyc Hasidic dynasty. She had nine siblings. Her parents, Alexander and Masza (née Norwind), ran a shop at 37 Nowolipki Street, later relocated to 40 Nowolipki Street. She attended the Jewish Yehudiyah high school at 55 Długa Street, where she was an outstanding student and also excelled in sports.

As a teenager, she joined the leftist Zionist youth organization Ha-Shomer Ha-Tzair. At first, she kept this fact hidden from her parents, who disapproved of the organization’s leftist orientation. In time, however, she gained their acceptance. She became a member of the “Bachazit” unit of Ha-Shomer, which also included Mordechai Anielewicz. In 1938, she took on the role of youth instructor, becoming greatly admired by the younger members.

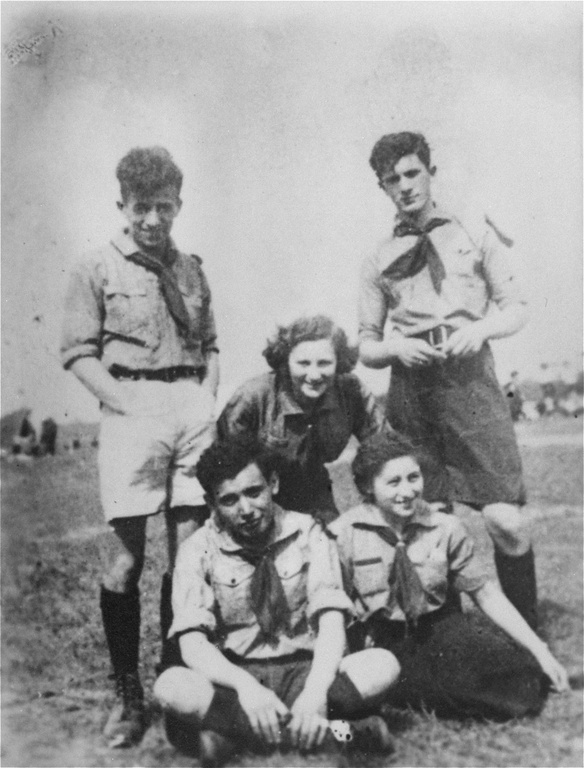

Group portrait of members of Ha-Shomer Ha-Tzair. In the back row, from left to right, are: Zvi Braun, Shifra Sokolka, and Mordechai Anielewicz. In the front, seated, are Moshe Domb and Rachel Zilberberg (“Sarenka”). Warsaw, Poland, 1938. | US Holocaust Memorial Museum courtesy of Leah Silverstein Hammerstein

After the outbreak of war, Sarenka, along with her younger sister Rut and Anielewicz’s friend Mosze Kopito, fled east to Lithuania, like many other Jewish activists. There, she joined Kibbutz Hamanof near the town of Kėdainiai, and later a kibbutz of Ha-Shomer members in Vilnius. Thanks to her position in the movement, she arranged for her sister Rut to emigrate to Palestine. She herself decided to stay and continue developing Ha-Shomer’s local structures. During this time, she formed a relationship with Mosze Kopito, and on February 22, 1941, their daughter Maja was born in Vilnius.

In June 1941, the German army attacked the Soviet Union and occupied Lithuania. Soon, the extermination of the local Jewish population began. From July, the Germans conducted mass executions in the Ponary forest near Vilnius. Mosze Kopito, who was working under a false name as a communist in a local factory, was betrayed by a coworker and shot by the Germans on the street as he went out to get milk for baby Maja.

Faced with mortal danger, Sarenka decided to entrust her daughter to a friendly doctor—a communist who ran an orphanage. Although this separation was heartbreaking, it gave the child a chance to survive. The girl lived under the assumed name Jadwiga Sogak and likely survived the war.

Rachel visited her daughter as often as she could. Eventually, however, she had to go into hiding along with 15 comrades from Ha-Shomer, including Abba Kovner and Jurek Wilner, in a Dominican convent near Vilnius. Professor Dina Porat, in her biography of Abba Kovner “Maavar Legisha”, writes that it was there that the idea of youth rebellion against the German occupiers was born. Kovner, Sarenka, and their companions realized that the massacres in Ponary were not isolated incidents but part of a systematic plan to annihilate the Jews. They knew they had to warn the Jewish community and call them to resistance.

For this reason, Sarenka returned to the Warsaw Ghetto to tell the Jews there about the Nazis’ plans for the so-called “Final Solution”. She was accompanied on this journey by Chajka Grossman. In her memoirs, Grossman recalled that, for safety, Rachel was disguised as her child—even though she was older than Grossman.

In the Warsaw Ghetto, Rachel lived at 40a Nowolipie Street. She worked in a small tailoring workshop with Mira Fuchrer and Towa Frenkel, and also in a shop at 34 Nowolipki Street with her mother. She immediately engaged in underground activities: writing reports, recounting German crimes in Lithuania, and calling for armed resistance.

Aliza Witis-Shomron, who joined Ha-Shomer Ha-Tzair as a teenager in the Warsaw Ghetto, recalled her first meeting with Sarenka:

“I remember clearly a gray September evening in 1941 at the Ha-Shomer Ha-Tzair branch on 23 Nalewki Street, when we received the first news from the Vilnius ghetto. (…) We all sat on the floor in that room, and before us stood a girl, maybe twenty-two years old. Her hair had silver strands—early signs of gray. In the dimming light, she looked beautiful, but her eyes were lifeless. She spoke:

(…) It was a terrible night. We—the members of Ha-Shomer Ha-Tzair—hid in one apartment. We listened for street sounds. We heard cars pulling up, then voices, screams, gunshots—heart-wrenching cries—the Germans were rounding up people, street by street. Where to? To a forest near the city, to Ponary—the execution site. Thousands of Jews have already been sent there. We have eyewitnesses who escaped and told us that men, women, and children are lined up at the edge of a pit and shot on the spot.

I came here to tell you this and to warn you. We have information about the liquidation of ghettos throughout eastern Poland, Ukraine, and Lithuania. We have decided to resist. (…) Abba Kovner drafted a manifesto calling for armed resistance against the Nazis. We decided that when our time comes, we will not die without a fight, and if we run out of weapons, we will spit in their faces.”

On April 19, 1943, the Germans launched the final liquidation of the Warsaw Ghetto. The Jewish fighters rose in armed resistance. Sarenka fought in two groups defending Miła Street and the corner of Zamenhof and Gęsia Streets. After initial surprise, the Germans responded with brutal repression: they searched streets and homes and set buildings on fire.

By early May, the fighting was concentrated around bunkers. On May 8, the Germans discovered the shelter at 18 Miła Street, where the headquarters of the Jewish Combat Organization (ŻOB) was located. Around 100 fighters and 200 civilians were hiding there. Rachel Zylberberg was among them. She died alongside Mordechai Anielewicz and a hundred other Jewish fighters.

Rachel’s parents and all eight of her siblings also perished during the Holocaust. Her daughter Maja likely survived. It is believed she may be living somewhere in Russia or Lithuania, unaware of her origins. If still alive, she would be 84 years old today.

Ofer Aloni, the son of Rut—Rachel’s only sister to survive the war—spent over ten years searching for Maja without success. He passed away in April 2025. He firmly believed that Sarenka was depicted on the Monument to the Ghetto Heroes in Warsaw as the woman turning her face away from the child in her arms.

For many years, the story of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising was told mainly through the lens of male leaders. The stories of women who played equally vital roles in the underground and armed resistance remained largely forgotten or marginalized in historical literature. Aloni’s discovery helped restore the memory of one of them, and Sarenka’s story stands as a symbol of the many forgotten women of the Jewish resistance.

Bibliography:

- Grossman Ch., “The Underground Army”, New York 1987

- Grupińska A., “Odczytanie Listy. Opowieści o powstańcach żydowskich”, Kraków 2003

- Neustadt M., “Chorban Wemered Shel Jehudei Warsza”, Tel Aviv 1946, from: https://surl.lu/pxfxyt

- Porat D., “Maawar legishmi. Parshat Haim Shel Aba Kovner”, Tel Aviv 2000

- Sefer HaPartizanim HaYehudim, ed. Chaika Grossman and Aba Kovner, Jerusalem 1958

- Witis-Szomron A., “Youth in Flames”, Warsaw 2013

- https://www.code2hope.net/sarenkam (accessed 02.06.2025)

- https://www.jpost.com/magazine/sarenka-unsung-hero-of-the-warsaw-ghetto-uprising-578520 (accessed 02.06.2025)