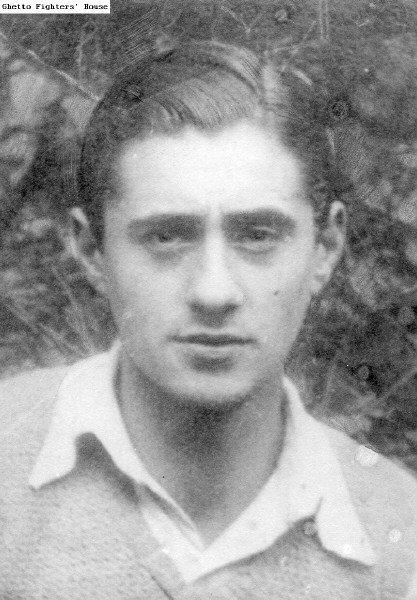

Lejb “Lutek” Rotblat (1918–1943)

Activist in Ha-Noar Ha-Tzioni and Akiba, member of the Jewish Combat Organization (ŻOB), an active participant in the Jewish resistance movement and a hero of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising.

He was born in Warsaw on October 14, 1918, into an assimilated Jewish family. The Rotblat family lived on Twarda Street, which also housed an orphanage (Twarda 27) directed by Lutek’s mother, Maria (Miriam). He lost his father at a young age and remained very close to his mother throughout his life.

In 1937, he passed his final exams at a Polish gymnasium and became a youth counselor in the Zionist youth organization Ha-Noar Ha-Tzioni, where he led the “Hagalil” chapter. After the outbreak of the war, he joined the Zionist youth organization Akiba.

Lejb (Lutek) Rotblat | Ghetto Fighters’ House

During the so-called Great Deportation Action, when Jews were forcibly sent from the Warsaw Ghetto to the Treblinka death camp, Lutek’s mother and a group of 80 orphan girls (aged 10–16) from the orphanage were among those being led to the Umschlagplatz. They managed to send a message:

“Save us. We are with our children, on the way to death.”

Hela Rufeisen-Schupper, a friend of Lutek’s from Akiba, saw Maria Rotblat from her apartment window among those being marched to the transfer square. When she brought this information to the headquarters of the Jewish Council (Judenrat), it was already known that the orphans and Maria were at the ramp of the Umschlagplatz. Lutek, together with Nachum Remba (an employee of the Council), pleaded with German officials for their release.

They managed to persuade the Germans by claiming the girls worked in workshops sewing German uniforms, and that their work was essential. A bribe and the prestige of wearing medical coats (which they had disguised themselves in) helped. The entire group returned safely to Twarda Street.

Lutek saved the orphanage girls several times, hiding them in gateways during street roundups. In August 1943, during the liquidation of the so-called “small ghetto,” the orphanage lost its premises. Lutek found a new location and, under the cover of night, organized the transfer of the children to a new address at 18 Mylna Street.

The new location, with a spacious attic and a hidden entrance behind a wardrobe, offered shelter not only to the orphans but to others as well. The actor couple Jonas Turkow and Diana Blumenfeld hid there for an extended period.

The idea of forming an armed resistance had been under discussion in Zionist youth circles since the beginning of the Great Deportation. Hela Rufeisen recalled in her book that Lutek initially had doubts—he feared for the younger ones:

“It’s clear that we, the counselors, should now join the fight; it’s our duty. But I don’t know if we have the right to drag all these young people with us—almost children. Maybe there’s still hope? Maybe they will survive?”

Soon, they all joined the Jewish Combat Organization (ŻOB). Tragically, during the second deportation wave in 1943, the children were sent to Treblinka. Maria Rotblat remained in the ghetto. Lutek dedicated himself fully to ŻOB activities: organizing arms purchases and production, weapons training, and lessons in urban combat tactics.

On February 22, 1943, he participated in the execution of collaborator Alfred Nossig. He created a concealed hideout for fighters in the apartment at 44 Muranowska Street, where he lived with his mother. It served as a recovery space for Arie Wilner after torture and also as a hiding place for Izrael Kanal.

Hela recounted a nighttime walk with Lutek in March 1943, during which they spoke about the emotions they felt preparing for armed resistance:

“Lutek expressed it in a few words: ‘There are no more orphans we were fighting for—my mother, I, and the others. I am free. I do what I can for the Combat Organization. That keeps me alive. Now I can look calmly at the stars in the sky.’”

On April 18, 1943, the eve of the uprising, Lutek was appointed commander of a combat group composed of Akiba members. They fought in the so-called central ghetto, defending the intersection of Nalewki and Gęsia streets.

On April 19, the uprising broke out. The Germans, attacking from the gate on Nalewki Street, were met with a strong counterattack by ŻOB units led by Lutek Rotblat, Zacharia Artstein, and Henryk Zylberberg. Using firearms, grenades, and Molotov cocktails, after two hours of fighting, they forced the Germans to retreat. This victory was especially significant because the losses were only experienced by the Germans.

Later that day, the Germans launched another assault on the defenders’ position at Nalewki and Gęsia. The Jewish fighters, low on ammunition, had to retreat to Kurza Street. Henryk Zylberberg was killed in the clash; Lutek survived.

When the Germans began setting the ghetto on fire, the fighters hid in bunkers, from where they launched ambushes and smuggled people out of the ghetto. The bunker at 29 Miła Street became the base for Lutek’s group, as well as those of Aron (Paweł) Bryskin and Lejb Gruzalc. It stored ammunition and housed the ŻOB radio.

On April 24, the house at Miła 29 was set on fire. Lutek and Aron Bryskin evacuated several hundred civilians to a bunker at 9 Miła Street. Hundreds crowded into its basements and courtyards. When that location too was endangered by fire, the fighters moved to another bunker at 18 Miła Street.

This bunker, previously built by smugglers, became the main ŻOB stronghold. There were around 100 fighters and 200 civilians inside, along with the ŻOB leadership.

At that time, Lutek’s mother and Hela Rufeisen were hiding in a bunker at 44 Muranowska Street, together with printers, Jewish Council staff, and historian Naftali Nusenblat.

During the fire and German assault on the building, Nusenblat was shot and died. Lutek returned for Hela and his mother. Tosia Altman accompanied them, holding a grenade and closing the march. The Germans were firing and throwing grenades relentlessly—the street crossing was deadly. Still, they reached the bunker at 18 Miła safely. However, it turned out to be only a temporary refuge.

A few days before the bunker was denounced, Hela left it on the order of Mordechai Anielewicz. She escaped through the sewers to the “Aryan side” carrying a message for Yitzhak Zuckerman.

On May 8, 1943, the Germans discovered the bunker entrance and released gas inside. Panic erupted. Two hundred civilians surrendered. The ŻOB staff and about 120 fighters refused to capitulate. Over a hundred died from poisoning or committed suicide.

Cywia Lubetkin, in her book The Holocaust and the Uprising, recalled the final moments of Lutek and his mother:

“Among the fighters in the bunker at Miła was Lutek Rotblat from the Akiba core, together with his mother. […] In the tragic moments of the German attack on the bunker, she asked him to kill her. He fired four times, and she still showed signs of life. Then, with the fifth bullet, he took his own life.”

On April 18, 1945, Lutek Rotblat was posthumously awarded the Cross of Valor by the Polish authorities.

Hela survived the war and emigrated to Israel. She died in 2017.

Bibliography:

- Barski [Gitler-] J., Experiences and Memories from the Years of Occupation, Wrocław, 1986

- Bernard M., The Uprising in the Warsaw Ghetto, Warsaw, 1963

- Grupińska A., Reading the List: Stories of Jewish Insurgents, Kraków, 2003

- Gutman I., The Revolt of the Besieged: Mordechai Anielewicz and the War of the Warsaw Ghetto, Jerusalem, 2013

- Lubetkin C., The Holocaust and the Uprising, Warsaw, 1999

- Rotem K.S., Kazik: Memoirs of a Jewish Combat Organization Fighter, Warsaw, 1993

- Rufeisen-Schupper H., Farewell to Miła 18: Memoirs of a Liaison of the Jewish Combat Organization, Kraków, 1996