Jews in the Warsaw Uprising: The fate of Szoszana Kossower

On 1 August 1944, the Warsaw Uprising began. There had been another uprising in occupied Warsaw – the first one broke out on 19 April 1943 in the Warsaw Ghetto.

By August 1944, the Jewish quarter no longer existed, and the overwhelming majority of Polish Jews, including the Jews of Warsaw, had been exterminated by the Germans. However, fugitives from the ghetto and elsewhere were still hiding in the city. To this day, there is no agreement as to how large this group was. The most common estimate is that there were as many as several thousand Jews in Warsaw at the time. Among them were dozens of fighters associated with the Jewish Combat Organisation (ŻOB) and the Jewish Military Union (ŻZW) who survived the fighting in the ghetto. Several hundred Jews, mainly from abroad, were held by the Germans in the Gesiowka concentration camp. Of the Jews hiding on the ‘Aryan’ side, some found permanent places of refuge, while others stayed under false identities and tried to stay out of sight of the occupiers or the blackmailers who were after them.

What happened to them after the outbreak of the Warsaw Uprising? How did the uprising affect their survival strategies? What emotions and feelings did the it evoke in them? How did Jews participate in the fighting? What were their motivations? Did they betray their true identity by joining Polish underground organisations? Can we identify individuals who were heavily involved in the uprising? Historians have been trying to find answers to these and many other questions for years. In doing so, they are often able to describe individual fates, but the bigger picture still escapes their grasp.

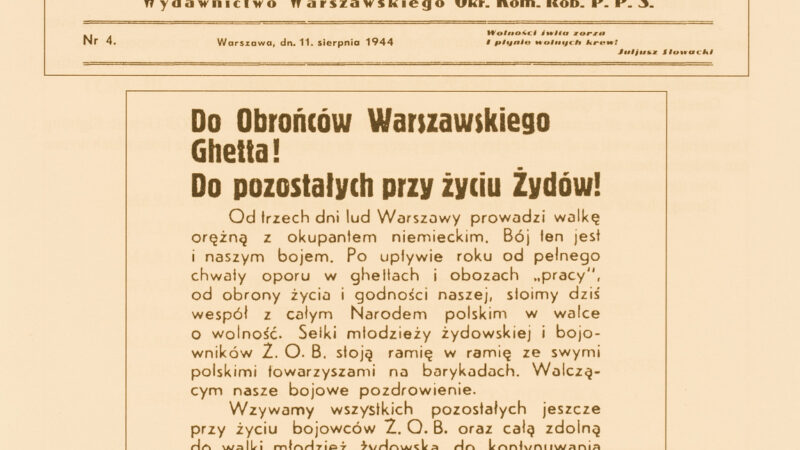

On 3 August, Yitzhak Cukierman issued a proclamation to members of the ŻOB, former ghetto fighters and to Jews hiding on the ‘Aryan’ side:

‘To the defenders of the Warsaw Ghetto! To the surviving Jews! For three days the people of Warsaw have been embroiled in armed battle against the German occupier. This is our battle, too. A year after the glorious resistance in the ghettos and “labor” camps, after the defence of our lives and dignity, today we stand together with the entire Polish Nation in the fight for freedom. Hundreds of Jewish youth and ŻOB fighters stand shoulder to shoulder with their Polish comrades on the barricades. To the fighters, we salute you. We call upon all the surviving ŻOB fighters and all able young Jews to continue the resistance and the struggle, which no one can stand back and watch. Join the ranks of the uprising. Through battle to victory, to a free, independent, strong and just Poland’.

In our day, we are unable to determine how many Jews were reached by this plea, and how many responded to the call and intended to join the fight. We do know for sure about the participation and commitment of the ŻOB platoon, which was part of the People’s Army. Its members participated in heavy combat in various parts of Warsaw, including the Old Town and Żoliborz. After the war, Cywia Lubetkin recalled: ‘Our groups were also aware of the political content of the uprising. But it was a war against the Germans’. Jews were not well regarded in every unit, however. On more than one occasion, for various reasons, they were denied the opportunity to join Home Army forces. This meant some of them never revealed their true identity or joined the People’s Army units. Cukierman wrote that there were cases of Jews being murdered by members of the underground forces: ‘Comrades from our group that fought in the ghetto joined in. Some were later murdered by the Germans, others by the Home Army’.

Among the Jewish fighters in the Warsaw Uprising were Yitzhak Cukierman, Tzviya Lubetkin, Marek Edelman and Samuel Willenberg. Some, such as Adina Blady-Szwajgier and Alina Margolis, were on first-aid duty.

Yitzhak Cukierman, Tzivia Lubetkin and Samuel Willenberg

The uprising had various consequences for the Jews. Yitzhak Cukierman recalled after the war: ‘We welcomed the outbreak of the uprising with a feeling I cannot describe; we felt that the moment of revenge against the Germans had finally arrived’. In turn, Tuwia Borzykowski reported: ‘We had mixed feelings aboutthe uprising. For some Jews, the it brought freedom (at least temporarily). After the ‘W’ hour, a Kedyw unit under the command of Lieutenant Stanisław J. ‘Stasinek’ Sosabowski (acting in concert with Jewish conspirators and soldiers Stanisław Aronson and Stanisław Likiernik) liberated around fifty Jews employed at the Umschlagplatz. Later in the uprising, on 5 August, the Zośka Scouting Assault Battalion stormed the ‘Gęsiówka’ concentration camp in Warsaw. They liberated nearly 350 Jews imprisoned there (mainly from abroad – Greece, Hungary or France). Most of them joined the insurgents. For some people hiding in various parts of the city, however, the uprising meant being exposed and having to flee. They were afraid that once the fighting spread, it would be too late to evacuate. Some feared an armed uprising and retaliation by the Germans, still recalling what the occupiers had done to the ghetto area.Nie będzie to jasne dla czytelników (a nie jest też dla mnie jasne).

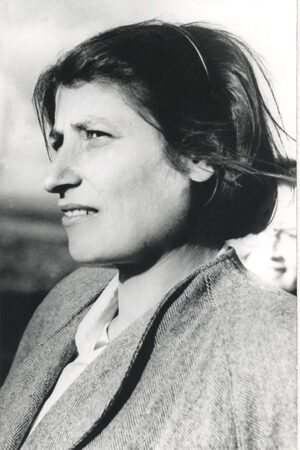

Shoshana ‘Emilka’ Kossower

One Jewish woman who took part in the Warsaw Uprising from the outset was Szoszana Róża Kossower. She was born on 10 April 1922 in Radzymin to a religious Jewish family. She was the youngest child of Josef and Sura Cypa, sister of Chana, Chaya, Esther, Michael and Shulim. Although the home in which she grew up was traditional ones, Kossower became involved in Zionism at a young age, following in her brothers’ footsteps. She became a member of Beitar, a right-wing Zionist organisation. Why did she join them and not, for example, Ha-Szomer Ha-Cair or Ha-Noar Ha-Iwri ‘Akiva’? The available sources give us no conclusive answers. Much of the information concerning the pre-war period is lost in the mists of time. It is not clear what school she attended, what shaped her, what she read. We do not know whom she befriended, what interested her, how her relatives reacted to her activities, or what exactly she did in Beitar. Was she planning a trip to Palestine? Was she preparing for it? What skills did she acquire in her organisation?

The Germans entered Radzymin on 24 September 1939. The town’s inhabitants (3,800 Jews at the time) had already tasted war earlier, when bombs fell on their homes. The exodus of individuals and entire families also began quickly – they fled towards the east, convinced it would be safer there. Time confirmed these assumptions. The occupiers quickly got organised in the city. Jews were subjected to anti-Semitic legislation and obliged to form a Judenrat and police force. At the end of 1940, a semi-open ghetto was established in Radzymin. Kossower remained in the town after the war broke out. She lived there with her family, studied, worked and tried to function within the occupation’s means. To support the household budget, she occasionally travelled to Warsaw to buy wool. Her trips continued until the outbreak of the German-Soviet war in 1941.

Her life changed again in 1942. In the spring of that year, the liquidation of the ghettos got underway. Aware of these events, Szoszana and her sister made their way to the Warsaw Ghetto. Perhaps they thought that its size gave it better chances for survival. They sought shelter for themselves and tried to set up a place for the other members of the family. While they were in Warsaw, the Radzymin ghetto was liquidated and the Jews living there were deported to the Treblinka extermination camp. Szoszana’s parents and many of her relatives shared this fate. Her brothers survived. Szoszana later helped them find shelter. We know little about her stay in the Warsaw Ghetto, how she survived the great deportation operation to the Treblinka death camp and her further fortunes after the deportations came to an end.

Over time, Kossower became involved in underground activities. Her good looks and, above all, her character traits, her openness and sense of a mission, were to her advantage. She cooperated with both the Jewish and the Polish underground. A former acquaintance of hers, Major Olgierd Ostkiewicz-Rudnicki – commander of the XII Łukasiński group in the 4th Region of the 1st District (Śródmieście) of the Warsaw Division of the Home Army – got her in contact with the Home Army. She operated as Emilia Rozencwajg, ‘Emilka’ or ‘Marylka’. Shoshana ‘Emilka’ Kossower came to join this battalion. Through her acquaintance with Barbara and Adolf Berman, she also collaborated with the Jewish National Committee. As she herself pointed out in an interview with Hanka Grupinska, she belonged to neither the ŻOB nor the ŻZW. ‘Being on the Aryan side, I didn’t realise whether it was the ŻOB or the ŻZW – I wanted to work, to do something. I didn’t imagine there were any organisations. I thought that everyone worked together’, she emphasised.

She acted as a courier. She organised escapes from the ghetto, and then from labour camps as well. Among those she helped to leave the Warsaw Ghetto were the writer Rubin Feldszuh and Rachela Auerbach. It was Szoszana Kossower who, together with Teodor Pajewski, participated in the operation to bring Emanuel Ringelblum out of the labour camp in Trawniki in the summer of 1943. After that, she helped organise weapons for the Jewish underground. As a courier, she went outside the Jewish quarter. She left the ghetto shortly before the uprising broke out. On 19 April 1943, she was in the countryside. On hearing of the uprising, she returned to the Warsaw, but was no longer able to get past the wall. From the ‘Aryan’ side, she helped as a liaison officer and intermediary to find shelter for those who had miraculously left the burning ghetto. She also supported family members in hiding. After the collapse of the uprising and the liquidation of the Warsaw Ghetto, she stayed in the city, remaining active in the underground.

During the occupation she took a nursing course. These skills proved useful after the outbreak of the Warsaw Uprising. The Home Army command, noting her previous involvement, assigned her more important tasks. Her cleverness, foresight and experience were put to good use – she continued to act as a liaison officer. She couriered correspondence and underground press. She fought in the Old Town. She helped lead people out through sewers. At times she also tended to the wounded at Ujazdowski Hospital. She was awarded the Cross of Valour and promoted to second lieutenant. It is difficult to determine how many people in the Polish underground were aware of her origins.

She left Warsaw on the day the Uprising capitulated, 2 October 1944. She was arrested and spent the rest of the war in a prisoner-of-war camp in Oberlangen (Stalag VI C) in the Reich. Surviving until the end of the occupation, she returned to Warsaw in 1946 and worked for some time at the Central Committee of Jews in Poland. In 1950, she left for Israel, where she started a family, lived and worked. She died on 18 June 2008 in Tel Aviv. On 27 April 2022, she was posthumously awarded the Commander’s Cross of the Order of Polonia Restituta.

Bibliografia

- Blady-Szwajger A., I więcej nic nie pamiętam, Warszawa 1994.

- Borzykowski T., Between Tumbling Walls, translated from Yiddish by M. Kohansky, Beit Lochamei ha-Getaot 1972.

- Cukierman I., Nadmiar pamięci (siedem owych lat). Wspomnienia 1939-1946, translated by. Z. Perelmuter, Warszawa 2000.

- Engelking B., Libionka D., Żydzi w powstańczej Warszawie, Warszawa 2009.

- Grupińska A., Po kole. Rozmowy z żydowskimi żołnierzami, Warszawa 1991.

- Grupińska A., Ciągle po kole: rozmowy z żołnierzami Getta Warszawskiego, Warszawa 2013.

- Grupińska A., Odczytanie listy: opowieści o powstańcach żydowskich, Kraków 2003.

- Radzymin [w:] Encyclopedia of camps and ghettos 1933–1945, vol. II Ghettos in German-Occupied Eastern Europe, Editor Martin Dean, 2012, s. 423-425.

- Szyba A., Szymaniak K., Splatanie historii [w:] Kwestia charakteru. Bojowniczki z getta warszawskiego, Ed. S. Chutnik, M. Sznajderman, Wołowiec-Warszawa 2023.