Agony in an ‘exotic’ hell: Greek Jews in KL Warschau

Greek Jews were sent to KL Warschau straight from KL Auschwitz, where they had lost their loved ones, often entire families. This was another ring of an ‘exotic’ hell for them. They worked in the bitter cold, amid the eerie ruins of the ghetto, under the supervision of SS sadists. Those who did not die of starvation were killed by typhus or German bullets. This is the story of their forgotten martyrdom.

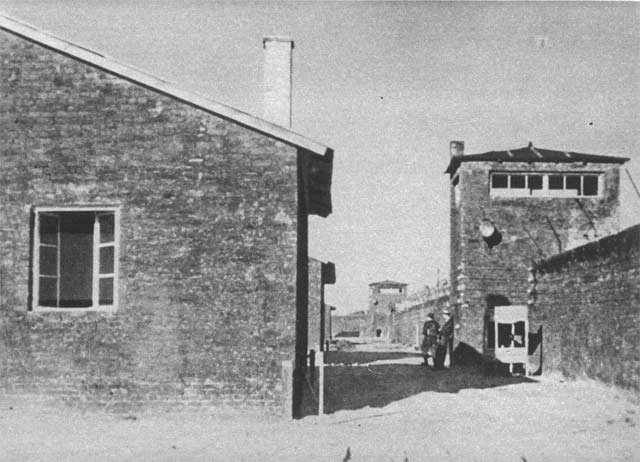

Right from the very first hours of the Warsaw Uprising, Home Army soldiers attacked the KL Warschau camp. ‘Gęsiówka’, as the camp was called, was located in the western part of the sea of ruins that remained of the Warsaw ghetto. It stretched along Gęsia Street, from Zamenhofa to Okopowa Street. Fenced off with barbed wire and barricades, and in some places with a wall as well, the camp contained twenty-one barracks for prisoners, as well as ten watchtowers and several bunkers. These meant the Germans were able to effectively repel the insurgents’ attacks during the first few days of the uprising, inflicting heavy losses.

Gęsiówka | Domena publiczna

However, the Polish soldiers did not give up. Their commanders knew that they had to capture this strategic stronghold in order to maintain the combat initiative. At the same time, they intended to free hundreds of Jewish prisoners, whom the Germans could have exterminated at any moment. And so, on the afternoon of 5 August, the insurgents of the Zośka Battalion launched their assault.

The attack was led by Lieutenant Wacław Micuta, commandeering a captured Panther tank. The vehicle turned from Okopowa onto Gęsia Street, and then entered the camp area at Smocza Street. It bulldozed two barricades, fired at the watchtowers, and forced its way through the camp gate. Right behind it, soldiers from the Alek and Felek platoons stormed in.

The Germans were completely taken by surprise – they had thought their comrades-in-arms were inside the tank. By the time they realised what was happening, it was too late to mount an effective defence. They fired a few rounds at the Panther and began to retreat. The insurgents were unable to immediately pursue the enemy.‘The barracks doors burst open under [the prisoners’ – ed.] pressure, and the entire space swarmed with people in striped pyjamas, rushing towards us with awful screams, waving their arms. We were thus separated from the fleeing Germans, as if by a living wall’, recalled Captain Ryszard Białous, commander of the Zośka battalion.

‘Everyone’s faces beamed with the joy of liberation. It was certainly greater than ours, clouded by the fact that, for the moment, we were helpless against the enemy. Our guns had to fall silent, and the Germans took advantage of this, fleeing swiftly to the Old Town,’ he added.

Among the 348 freed prisoners, more than half were from Hungary. However, the Poles were much more interested in a group of several dozen Jews who spoke another language that was completely incomprehensible. They were from Greece, mainly Thessaloniki. They had been in KL Warschau the longest. They had been through hell.

Kidnapped from ‘Mother Israel’ to Auschwitz

Located in north-eastern Greece, Thessaloniki was one of Europe’s largest primarily Jewish cities from the sixteenth to the early twentieth centuries. They settled there in large numbers after their expulsion from Spain in 1492. For centuries, the city became the main centre of Sephardic culture. It was even called the ‘Mother of Israel’. Before the outbreak of World War II, about 50,000 Jews lived there.

In April 1941, Thessaloniki was occupied by German troops, who immediately began persecuting the local Jewish community. They started with beatings, forced labour, mass theft, extortion and expropriation. Then, in early 1943, the Jews were briefly confined to two ghettos within the city. Between March and August 1943, over 45,000 were deported to the Auschwitz concentration camp.

On the way, the Thessaloniki Jews suffered greatly. They were crammed into cattle cars, 100 people at a time, for eight or nine days. They were wracked with thirst – the Germans gave them no water. The end of their gruesome journey came at the ramp in Auschwitz II Birkenau, where SS men dragged them out and beat them indiscriminately, to the sound of screams and gunshots.

This is how twenty-seven-year-old hairdresser Zako Poliker, accompanied by his pregnant wife Sylia and son Mordechaj, described their arrival at the camp:

‘The little one (…) was in my arms the whole time, unconscious, half dead. In one of those terrible moments, I don’t know when or how – when the crowd, mad with terror, surged forward to the exit – the child slipped from my arms! A huge wave of people, trampling everything beneath them, engulfed me, my family – our baby – everything, everything! I couldn’t comprehend anything anymore (…). All I could hear was the terrible screams of the Germans (…). In an instant, everything was gone – Sylia and the child – and perhaps myself as well?’

Most Jews from Thessaloniki were immediately sent to the gas chambers. Zako was among those who were spared. Six months later, in the autumn of 1943, he and a group of several hundred compatriots were put on a train again, headed for Warsaw.

An inferno in Gęsiówka

In July 1943, a few weeks after the uprising was put down, the Germans began carrying out Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler’s order to develop the former Warsaw ghetto area. By this command, all the buildings there were to be demolished. A 180-hectare park was to be created on the cleared land. It was originally assumed that the entire operation would conclude by 1 August 1944.

Four German companies were entrusted with implementing the project. The labour was carried out by Jewish prisoners brought from Auschwitz, supported by about a hundred Polish workers. The former were hand-picked. They were mainly foreigners who did not know Polish, in order to make it extremely difficult for them to communicate with their surroundings. And so, in the summer and autumn of 1943, around 3,700 Jews, most of them young men from Belgium, France, Germany, Austria and, above all, Greece, were transported to Warsaw.

The Thessalonians arrived in Warsaw in several waves. The first group, numbering over 500 people, arrived on 31 August. The next group, of around 200 people, arrived at the end of October. The third and largest group arrived in November. It consisted of around 850 Greek prisoners.

The Jews were placed in KL Warschau – a newly established concentration camp, built, as described above, on grounds adjacent to the former military prison complex at 22 Gęsia Street. They joined 300 German criminals who had been brought there from the Mauthausen camp. Their task was to assist the SS in supervising the rest of the inmates, as kapos, blockälteste (block seniors) and brigadiers.

The new camp terrified the Greeks. It was located around grim ruins, which gave the stench of death. In addition, the conditions were extremely harsh. According to one of them, Abraham Mosse, the first wooden barracks had to be built by the prisoners themselves. The buildings were overcrowded and dirty, which encouraged the spread of lice and, with them, infections.

The accounts show that Greek Jews, accustomed to the mild Mediterranean climate, were particularly affected by the low temperatures in Poland’s autumn and winter. This was exacerbated by the fact that they spent most of the day outdoors, in only their striped uniforms and wooden clogs. The vast majority of prisoners worked on demolishing houses in the ruined ghetto. With no work gloves – equipped only with shovels and pickaxes – they cleared away bricks, handing them over to Polish workers. The latter transported them to the ‘Aryan’ side. Every now and then, they came across the bodies of those killed in the ghetto uprising. They dragged them to the camp, where they were incinerated.

As in all concentration camps, KL Warschau provided only starvation rations. ‘A little watery soup at noon, a piece of bread with a portion of margarine the size of a sugar cube in the evening’, recalled Poliker. The prisoners did what they could to supplement their diet. Any valuables found in the ruins, or even on the bodies of those killed in the bunkers, were exchanged for food – bread, sugar, bacon or sausage – from Polish workers. This practice was forbidden and had to be carried out with extreme discretion. If discovered by a German guard, both parties to the transaction faced death.

Yet as in every camp, Jews did not have to commit ‘offences’ to incur the wrath of the SS men. There was no shortage of brutes and degenerates among them, such as the first camp commander, forty-five-year-old Westphalian Wilhelm Göcke. He examined the Jews’ teeth very carefully. As soon as he noticed one of them had a significant number of gold teeth, he and his trusted aide would take the unfortunate man ‘for a walk’ into the ruins. There they would kill their victim and extract the precious metal from his still-warm body. They then announced they had ‘been forced to shoot’ because ‘the prisoner had tried to escape’.

The typhus epidemic in KL Warschau

However, the biggest killer of prisoners at KL Warschau was a typhus epidemic. It broke out in January 1944 and lasted until March. Dozens of people died every day. ‘The camp administrators were indifferent, there was no care for the sick whatsoever. On the contrary, if an unfortunate patient had gold teeth, he was killed before the others’, recalled Jacques Otidett, one of the Jews from Thessaloniki.

Typhus claimed Zako Poliker’s last family member. Jehuda, his brother, who had survived all the hellish months in occupied Poland alongside him, died while he was working in the ghetto ruins. “When I returned (…) my fellow prisoners told me that Jehuda had been thrown out the window onto a pile of corpses. Snow was falling and covering the huge pile!” he recalled years later.

The epidemic killed about two-thirds of the prisoners at KL Warschau. This made the Germans decide to replenish their labour force. In April and June, they brought in several transports of Jews, totalling about 3,000 people. Hungarians were by far the most numerous among them, becoming the largest ethnic group in the camp.

Prisoners of Gęsiówka, August 1944 r. | Yad Vashem

The Tragedy of Saul Senor

One of the few lucky ones who managed to survive the typhus outbreak was eighteen-year-old Isaac Senor. The young man recovered solely through the selfless efforts of his resourceful older brother, twenty-nine-year-old Saul.

He was an extraordinary person. A lawyer, polyglot, and director of a bank in Thessaloniki. In KL Warschau, he was a leader of the Greek prisoner community. As the survivors’ recollections unanimously attest, they lived as a group and supported each other to the best of their ability.

Saul worked in a team that transported clothes from the camp to Winter’s laundry at 85 Leszno Street, under the escort of SS men, of course. Twenty-year-old Ester Orył, a Jew from Serock, was working on ‘Aryan papers’ there. The young woman – according to some accounts, she had fallen in love – decided to help the Greek man escape. It is unclear what the escape plan was. Zako Poliker wrote that Senor changed into civilian clothes in the laundry. He intended to leave the premises in this disguise, but was spotted by an SS man. First, there was a scuffle. The Jew allegedly knocked the German to the floor and rushed to escape. However, the guard recovered and shot him.

The wounded Saul was taken to the camp infirmary. After a few weeks, he recovered. The camp commander decided on a severe punishment. At noon, on 18 June, Senor was hanged in front of the assembled prisoners of the Gęsiówka camp. All the Greeks present in the square at the time remembered this tragic moment. They also remembered that one prisoner fainted at that moment. Isaac, the younger brother of the murdered man, could not bear the sight of this nightmare.

Evacuation and the Warsaw Uprising

In July 1944, Soviet troops were approaching Warsaw. On 27 July, the Germans decided to evacuate the camp. They acted with cruelty. First, they shot over 400 sick and debilitated prisoners. The majority of the rest, including Zako Poliker, were forced to walk to Żychlin station, about 100 kilometres from Warsaw. There they were loaded onto trains and transported to the Dachau concentration camp. Many did not survive the journey – they died of exhaustion and from German bullets. According to the estimates of Steven Bowman, a researcher of the extermination of Greek Jews, about 280 survived this ordeal.

According to Bowman, forty-one Jews from Thessaloniki were among the prisoners of KL Warschau liberated by the insurgents on 5 August. A significant number of them joined the ranks of the fighters. Most were assigned to auxiliary services, e.g. helping to build fortifications. Others, such as Jacques Otidett and a group of his friends, were given weapons. They travelled as insurgents from Wola to the Old Town and then through the sewers, to Śródmieście. At least a dozen Greeks survived until the uprising capitulated. The rest were killed.

Gęsiówka, August 1944 r. | IPN

Bibliography:

- Stefania Zezza, „We are a strict, iron group. From Salonika to Warsaw via Auschwitz” [w:] „Sephardic Horizons”, Issue 3-4, Vol. 10, 2020.

- Steven Bowman, „The Agony of Greek Jews”, Palo Alto 2009.

- Relacja Jacques Otidett – Archiwum ŻIH, sygn. 301/2033

- Relacja Zako Polikera – Archiwum ŻIH, sygn. 301/7019

- Relacja Edwardy Orylo-Glaser (Cesia Glaser) – Archiwum ŻiH, Sygn. 301/2782

- Edward Kossoy – „The Gesiowka Story – A little known page of Jewish History Fighting”, Yad Vashem Studies, nr 32, 2004

- „Karta”, nr 99, 2019.

- Bogusław Kopka, „Konzentrationslager Warschau. Historia i następstwa”, Warszawa 2007.

- Relacje greckich Żydów, w tym Isaaca Senora i Abrahama Mosse, z USC Shoah Foundation Institute for Visual History and Education (dostępne na Youtube – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OLPeeE_LB2Q).