Wiera Gran (1916-2007)

Singer, cabaret actress, star of the Warsaw Ghetto stage.

Warsaw, a police station in the Praga district, 1945.

A young woman quickly approaches the officer on duty. She nervously rambles: “I heard a dumb story… Radio… Szpilman… collaboration with the Gestapo… rumors… […] please help me!” The officer calmly notes her name, surname, and address and promises to pass the matter on to the authorities. Shortly thereafter, on April 30, militiamen are standing at the door of her apartment, insistently demanding that she open up. Without any explanation, they arrest her and take her to the headquarters of the Ministry of Public Security (MBP) at 7 Sierakowskiego Street, in the building of the former Jewish Academic House. She is repeatedly interrogated and tortured. The woman consistently testifies that she is innocent.

At the same time, other witnesses testified before officials of the Ministry of Public Security to explain whether the accused, Wiera Gran (married name Jezierska), was guilty of collaborating with the Germans during the war or not. The case of the famous singer, who voluntarily reported to the Ministry of Public Security to explain her occupation-era story, was soon taken over by the Special Criminal Court, which summoned further witnesses. At the same time, the Union of Polish Stage Artists (ZASP) conducted a similar investigation to determine whether Wiera Gran would be allowed to perform on stage.

The case was pending until the fall of 1945. In October, the ZASP disciplinary committee ruled: “The behavior of Ms. Wiera Gran-Jezierska during the German occupation […] was beyond reproach.” The ruling bears the sweeping signature of the head of the court and widely respected artist Aleksander Zelwerowicz. Prosecutor Rudzewicz, who had been handling her case before the Criminal Court, soon requested that it be dismissed. As he explained: “considering the charges are based not on specific facts, but on vague and unsubstantiated allegations, the investigation should be discontinued.” The judge agreed with the prosecutor’s motion, and on November 26, 1945, “in the absence of criminal elements,” he dismissed the case against Wiera Gran-Jezierska.

Such investigations were not unusual. Proceedings to determine whether a person had committed crimes during the war or collaborated with the occupiers were commonplace. Usually, an acquittal or dismissal closed the case and allowed the accused to return to normal public life. However, this case was far from ordinary.

Wiera Gran was an exceptional figure. She was born in 1916 as the daughter of Elias and Liba Grynberg. Her father died when Wiera was three years old. Along with her two elder sisters, Hinda (Helena) and Marja (Maryla), she was raised by her single mother. In the 1920s, they lived in Wołomin, in a modestly furnished rented apartment. Circumstances forced Wiera to start working at a very young age—before her tenth birthday, she was put to work in a knitting factory, mending sweaters and stockings. She had been interested in music since childhood.

In 1931, she and her mother and sisters moved to Warsaw, to 8 Elektoralna Street, on the corner of Orla Street, where they all lived together in one room. Despite their poverty, Wiera was able to continue her education—she attended middle school at 12 Rymarska Street, and later managed to get into Irena Prusicka’s renowned dance school. Years later, she recounted that Prusicka, aware of her financial situation, did not charge her tuition fees. From this school, she went on to work as a dancer at the Paradis restaurant.

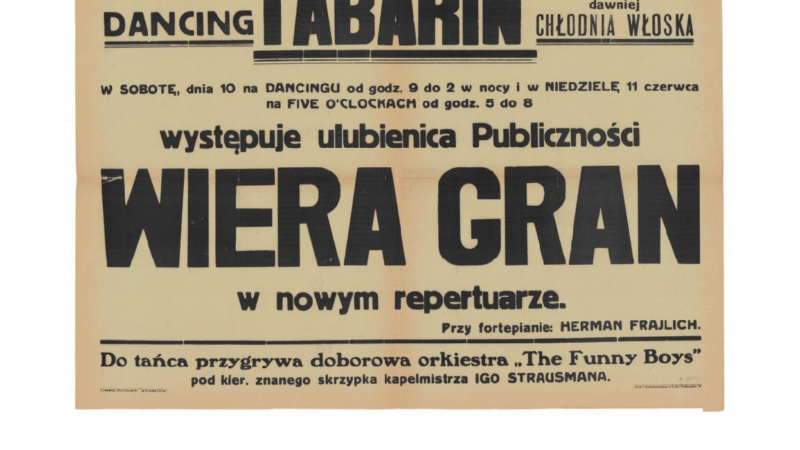

A traffic accident changed the course of her career. She broke her pelvis and was unable to dance, so she focused on singing. Her low, mellow alto voice attracted the attention of listeners and she quickly gained a devoted audience. She recorded her first albums in 1934, and her performances at Paradis began to be advertised in the press. At that time, she experimented with various stage names, such as Sylvia Green, Wiera Green, and Mariol. She quickly abandoned these, however, in favor of Wiera Gran. her popularity grew, more and more venues sought her performances, allowing her to set her fee as she pleased.

Her initial fee of five zlotys per performance quickly rose to twenty-five, and eventually to 150. She could earn more in one evening than the average worker received in a month. She performed regularly at Cafe Vogue at 7 Złota Street and gave weekly concerts on Polish Radio. In 1936, she moved with her family from a sublet room to an elegant apartment in a tenement house at 40 Hoża Street. Years later, she recalled: “I earned very well and had plenty of work.” She spent her last prewar vacation at the Grand Hotel in Sopot. After her vacation, she planned to go to Paris for guest performances.

However, she remained in Warsaw. Fortunately, her family did not suffer during the siege of the city. In the first weeks of the German occupation, she decided to head east, to areas then under Soviet occupation. Her companion during this period was a doctor she had met shortly before, Kazimierz Jezierski, two years her senior. Over time, they began to called a married couple, although it is unclear whether they actually did get married. After the war, Kazimierz testified: “I did not marry my wife, and I lied so that it would not come out that I was living with Wiera Gran unwed.” In Lviv, Wiera was hired by the Marysieńka and Stylowy theaters, and her performances soon became very popular. When the theaters were closed down, Wiera had to decide whether to join a troupe that would perform in the USSR or return to the General Government controlled by the Germans.

She chose the latter option. She had a short stay in Krakow, but when a ghetto was created there in March 1941, she returned to Warsaw and joined her mother and sisters trapped in the ghetto. Her husband also returned to Warsaw, but remained outside the ghetto walls. She sometimes met him in the Court building in Leszno. Wiera quickly found her ffeet in the ghetto and began performing in cafés, most often in the famous Sztuka Café at 2 Leszno Street. Years later, she prided herself in having promoted this venue: “It’s hard to believe what happened at Sztuka when I started performing there. That small café, which customers stumbled upon by accident, suddenly became a sensation.” She went on to recount how she attracted many other artists to Sztuka, such as her piano accompanists, Władysław Szpilman and Adolf Goldfeder, and poets Józef Lipski and Władysław Szlengel, who wittily commented on the current situation in Żywy Dziennik. She was probably exaggerating a fair bit, but she was indeed a popular artist, and her fees still allowed her to live a fairly comfortable life.

After the war, Gran liked to reminisce about her social activities—organizing a recital for the sick musician Leon Boruński or creating the “Detention Room” for street children at 12 Nowolipki Street. In reality, as other accounts indicate, she was not so much an organizer as an artist supporting these initiatives, donating part of her salary to them. In addition, she probably campaigned on behalf of those in need, thus coming into contact with prominent entrepreneurs in the ghetto. One of them was the respected baker Dawid Blajman, whom she persuaded to donate bread to the Detention Chamber. She also reached out to people with a much worse reputation—the well-known collaborator Abraham Gancwajch and two wartime profiteers close to the Germans: Moryc Kohn and Zelig Heller. As she testified in court, she visited Gancwajch in order to “sell tickets for charity events or to obtain aid for actors dying of hunger,” while Kohn and Heller were to generously support the Detention Chamber. However, many interpreted these contacts as proof that Gran was also in the service of the Germans. Her private performance at the home of another collaborator, one Szymonowicz, reinforced these suspicions. Gran never managed to untangle herself from these suspicions—they clung to her for the rest of her life.

In August 1942, when the Germans were sending daily trains from the ghetto to the extermination camp in Treblinka, Gran crossed the walls and went into hiding with Kazimierz Jezierski. Her husband’s connections allowed them to stay with a number of friends for a few days at a time. After about two months, they found a stable place to live and hid for the rest of the occupation in Babice, near Warsaw, where Jezierski worked as a doctor. Wiera tried to get her sister out of the ghetto, but the outbreak of the ghetto uprising in April 1943 thwarted her plans. In June 1944, she gave birth to a son, Jerzy, who died a few months later. Until the Red Army entered Warsaw, she stayed in Babice, and only visited Warsaw sporadically.

The rest of the story—her arrest and the aborted trial—has already been described. It seemed the matter had been settled, and in the fall of 1945 she could return to the stage.

In November, she performed on Polish Radio, giving her first concert after the war. In the following months, she performed throughout Poland—numerous posters from her performances in many cities have survived. However, she still felt threatened. Years later, she maintained that Władysław Szpilman and Jonas Turkow were constantly campaigning against her, alleging her collaboration, which made her feel the need to clear up the matter completely. In 1947, she applied to the Ministry of Justice to review her case. At the same time, proceedings were underway before the Social Court of the Central Committee of Jews in Poland, which were widely reported in the press. Numerous witnesses were heard in both cases. Once again, the prosecutor found no evidence of a crime in their testimonies and argued in his motion to dismiss the case: “Apart from these testimonies and the ‘negative opinion’ of Wiera Gran cited by several witnesses, no concrete evidence has been gathered. […] It must be concluded that a few instances of being in the company of Gestapo officers cannot constitute evidence of a person’s collaboration with the Gestapo.” The Social Court came to a similar conclusion and moved to acquit Wiera Gran in April 1949.

These verdicts failed to dispel all doubts, as it was still unclear whether her “negative reputation” was at least partly justified. Gran still felt mistreated by her critics and, over the following years, developed a morbid conviction that Szpilman and Turkow were constantly trying to ruin her career.

In 1950, she left for Israel, separating from her husband, Kazimierz Jezierski. For a long time, she was unable to settle anywhere. She left Israel for France, then Venezuela, and then returned to France. Then she resettled in Israel, only to return to France. Although she constantly tried to escape the rumors circulating about her, she probably unwittingly fueled them as well. Her musical career suffered as a result of her constant moving around, as she was forced to take new jobs. It was only in Paris that she found steady employment. Over the next few years, she traveled the world giving concerts, until she ended her career around 1970. Later, she continued trying to clear her name, in part through a trial that dragged on throughout the 1970s in Israel. She kept in constant contact with many scholars and tried to convince them of her innocence. In 1980, she published her autobiography, Sztafeta oszczerców (The Relay Race of Slanderers). The copy of this autobiography I used has a handwritten dedication: “To Mr. Władysław Bartoszewski, with respect and a request for criticism. Wiera Gran, Paris, June 1981.”

She died on November 19, 2007, in Paris.

Bibliography:

1. Gran Wiera, Sztafeta oszczerców, Paris 1980.

1. Tuszyńska Agata, Oskarżona: Wiera Gran, Kraków 2010.

1. AIPN, District Court Prosecutor’s Office in Warsaw, Files on the case of Wiera Gran-Jezierska, IPN GK 453/739.

1. AŻIH, Social Court, Case files. Wiera Gran-Jezierska, 313/36.