‘There is nothing more telling than numbers’: Victims of the ‘Grossaktion’

The perpetrators of genocides often pay little attention to the number of people murdered. The ultimate act of dehumanising the victims is to completely strip them of their subjectivity, to the point where they become a nameless mass rather than individuals with names, surnames or even numbers.

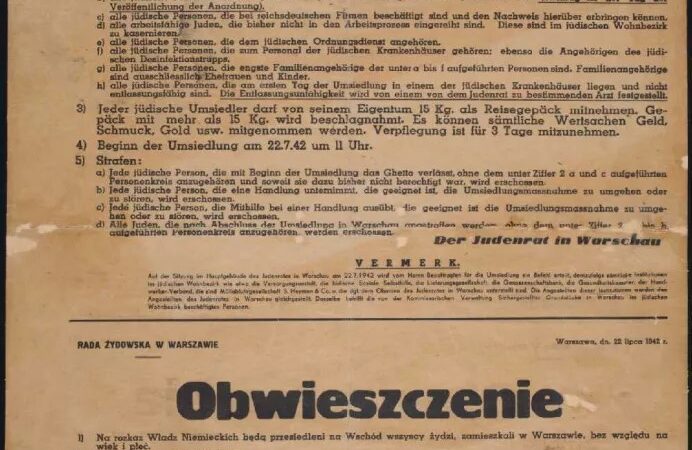

In the early morning hours of 22 July 1942, several vehicles pulled up in front of the building at 26 Grzybowska Street, where the headquarters of the Warsaw Jewish Council were located. A group of uniformed Germans, headed by Hermann Höfle, chief of the ‘Aktion Reinhardt’ staff, got out of the vehicles to meet with Adam Czerniakow, the chairman of the Judenrat, and a group of councilors. Marceli Reich-Ranicki, a well-known cultural critic after the war who was present at the meeting, recalled that the participants could hear Johann Strauss waltzes played by the SS men waiting in the car. Höfle commenced the meeting by announcing: ‘You should be aware that the number of Jews in Warsaw is too large’, after which he dictated the ordinance for the deportation, which was to begin the same day. According to his instructions, the Jewish Council was to ensure that ‘every day, starting from 22.7.42, 6,000 people were to be delivered to Umschlagplatz by 4 pm at the latest’. On the same day, the first transport of Jews to Treblinka left Warsaw.

The extermination in the Warsaw Ghetto began. Over the next two months, hundreds of thousands of Jews were deported from Warsaw to the Treblinka extermination camp.

Gustawa Jarecka, a writer living in the ghetto in the autumn of 1942, attempted to describe how the action went, recalling the events she had witnessed as an employee of the Judenrat. In her introduction she warned: ‘As a matter of fact, there is nothing more eloquent than numbers!’ Despite her plea, the number of deportees from Warsaw in the summer of 1942 has not yet been thoroughly researched, and wildly divergent estimates can be found in the literature. This article aims to outline the results of research to date, and to narrow down the range within which the number of deportees may fall.At the outset, we should point out that the perpetrators of genocide often pay little attention to the number of those they murdered. A conclusive way of dehumanising victims is to completely deprive them of their subjectivity, so that they become a nameless mass rather than individuals with names, surnames or even numbers. This thought was expressed more clearly by the former commandant of the Treblinka death camp, Franz Stangl, who, while serving his life sentence, spoke to investigative journalist Gitta Sereny:

[Sereny] – So you didn’t see them as human beings?

[Stangl] – Cargo, he said in a colourless voice. They were cargo. […]

[Sereny] – There were so many children among them, didn’t you think about your own at the time, about how you would feel in their parents’ place

[Stangl] – No, he said slowly, I don’t think I ever thought about that. He paused for a moment. ‘You see,’ he continued, still with that great seriousness and apparent desire to find a new truth in himself, ‘I rarely saw them as individuals. They were always one great mass to me.’

This approach was also reflected in how the deportees from Warsaw were counted. As Gustawa Jarecka wrote: “The deportees were counted as they were ordered to enter the wagons. The numbers on the individual wagons were noted down, probably not very accurately, with chalk. These were, in turn, written down by the Order Service. A few dozen people could always fall through the cracks’. Mieczysław Brzeziński was responsible for keeping this count. As the anonymous author wrote, ‘more accurate data is in the possession of the Regional Order Service engineer Brzeziński (unless he has intentionally falsified it). For he was in charge of the loaders’ group’. It is most likely the list based on his notes that has been preserved in the Underground Ghetto Archive – the data contained therein was described as semi-official or official. This data was continuously passed on to both the management of the deportation operation and the German civil authorities, which is why it was also referred to as German data. For the purposes of this article, it will hereinafter be referred to as the ‘loaders’ list’.

According to this summary, a total of 227,954 people were deported from the ghetto to the Treblinka death camp between 22 July and 21 September, while a further 11,580 were sent to the transit camp (‘Dulag’). However, this figure cannot be accepted uncritically, as the Jewish authors of The Liquidation of Jewish Warsaw report, written in the autumn of 1942, points out: ‘the figures in the various columns […] of the table are taken from German sources, tending towards a biased reduction, and should be taken as a minimum tally that deviates from the actual state of affairs’. This remark is unclear – it is not clear why the Germans would be interested in understating the number of deportees. The authors of The Liquidation of Jewish Warsaw further pointed out the lack of data on deportations on several dates (19–24 August, 26 August, 11 September 1942), They supplemented the entries for these periods with estimates: ‘presumably 20,000’, 3,000 and 5,000. Furthermore, the authors of the report omitted data for 21 September (2,196 people), the last day of this deportation. Thus, they arrived at a figure of 251,795 deportees; when supplemented by the data for 21 September, we get a figure of 253,991. However, it escaped the authors of The Liquidation of Jewish Warsaw that the ‘loaders’ list’ does not provide the number of deportees for 1–2 September, and for those days they did not provide their own estimates.

Findings to date

The data derived from The Liquidation of Jewish Warsaw is assumed by some historians to be reliable. Among them are Israeli death camp researcher Yitzhak Arad and Polish historian Ruta Sakowska, who, however, allows for the possibility that the estimate should be raised. Israel Gutman, on the other hand, considers these figures to be underestimates, assuming that 265,000 Jews were deported in the summer of 1942. A different conclusion was reached by two researchers, Tatiana Berenstein and Adam Rutkowski, who used demographic data to develop several estimates of the number of Jews in Warsaw on the eve of deportation, the number of escapees outside the ghetto walls, and those remaining after deportations in the ‘residual ghetto’. Depending on the scenario, the authors estimated that from 246,000 to over 280,000 Jews were deported between July and September, considering the upper end of this range (270–280,000) to be the most likely. Even higher figures are presented in The Liquidation of Jewish Warsaw, which, in addition to presenting data from a ‘loaders’ list’, insists on a figure of 300,000 deportees. The Stroop Report, on the other hand, settles on a figure of 310,322 deported in the summer of 1942. Most historians consider these figures to be either exaggerated or to represent the total personal losses of the ghetto, including deaths (both natural and from gunshots) and people sent to forced labour by the ‘Dulag’. If this were the case, the number of deportees to the death camp at Treblinka would exceed 280,000. Polish literature, including the work of Bernard Marek and studies by Barbara Engelking and Jacek Leociak, often cites a figure of 280,000 people deported to Treblinka and an estimated loss of 300,000 in the Warsaw Ghetto during the uprising.

Estimations based on deportation notes

Few researchers have allowed for the possibility that fewer than 254,000 deportees is realistic. However, the possibility cannot be dismissed out of hand. The additions to the ‘loaders’ lists’ made by the authors of The Liquidation of Jewish Warsaw raise some doubts, particularly concerning the period of 19–24 August, for part of which the Hermann Höfle unit responsible for the extermination of Jews was absent from Warsaw – they were organising deportations from other towns in the Warsaw district. It is not clear on which of these days trains to the Treblinka extermination camp departed from the railway siding at Umschlagplatz. In the years directly after the war, Tatiana Brustin-Berenstein suggested the six-day gap (19–24 August) was due to a pause in deportations, a view that was quickly disputed. Cross-referencing with Abraham Lewin’s diary shows that the break may have lasted from 19 August (on that day Lewin recorded: ‘Today there is no “action” in Warsaw, the gang went to Otwock’) to 21 August (as soon as on 23 August he noted: ‘Yesterday was the thirty-second day of the bloody “action”. It has not been aborted’) at most. This would mean that the break lasted at most three days – for the other three days, the transports were most likely leaving. About 4,000 Jews were deported by train during this period of action, so between 19 and 24 August, it was probably closer to 12,000 than 20,000 people were deported, as the authors of The Liquidation of Jewish Warsaw suggest.

Another gap in the deportation list was from 28 August to 2 September 1942, when the deportations are said to have stopped. The halt in the operation is confirmed by German materials. Indeed, from 28 August onwards, the Treblinka extermination camp stopped receiving new transports, as the previous commandant, Imfried Eberl, had caused a bottleneck of several trainloads of Jews, and the camp area was strewn with unburied corpses, making it impossible to deceive new arrivals that they would be put to work after their ‘bath’. It is not clear, however, on what day this interruption concluded. A roundup had already been carried out in the ghetto on 1 September, but due to the lack of wagons, the Jews were confined to the Umschlagplatz overnight. That night Warsaw was bombed by the Soviet air force, and in the confusion, some Jews escaped from the Umschlag. The following day, the blockade of the Fritz Schultz and Walter Többens plant was resumed, from which ‘several thousand workers were taken’. It is not clear whether the transport was sent from Warsaw that day, or if the Jews were dispatched the following day, together with those captured on 3 September.

If one assumes that the ‘loaders’ counted the deportees accurately, then their number would have to be estimated slightly below the figure given in The Liquidation of Jewish Warsaw, which is overestimated for the period of 19–24 August. Thus, the minimum estimate of deportees should be around 245–250,000.

Estimations based on demographic data

In February 1942, the last census was carried out in the ghetto before the deportations, determining the number of inhabitants at the end of January. It showed that there were from 369,000 to 377,000 people in the district at that time. Between the end of January and the end of June, nearly 21,000 deaths were recorded in the ghetto, around 4,000 Jews were resettled there from the Reich, and a similar number from towns in the eastern part of the greater Warsaw area. Thus, the number of Jews in the Warsaw Ghetto at the end of June should have been between 356,000 and 364,000. The first of these figures is confirmed by the number of rations cards issued for July 1942 (355,514). By the time the deportations began, just over 2,000 more people had died. If one subtracts from this figure (353,000) the number of ghetto escapees, people taken to labour camps, those who died in the district and the ghetto population after the deportations – one arrives at the number of people actually deported.

It remains difficult to determine the ghetto population at the end of the deportations. In the final phase of the deportations, thirty-odd thousand ‘life numbers’ were distributed – according to official German statistics, 34,969 Jews remained in the ghetto. In addition, a number of ‘wild cards’ remained in the ghetto – people residing illegally, often hidden in working family members’ flats or occupying deserted flats in buildings assigned to none of the companies operating in the ghetto. A census of the ghetto’s inhabitants was carried out in October 1942, but it was based on the inhabitants’ own declarations. Its authors wrote: ‘the question of declaring or concealing the fact of one’s residence arose for many people […]. This issue was resolved on an entirely individual basis; there were no instructions from the authorities in this regard, and the Jewish Council did not provide any guidance either’. Only a certain number of ‘wild cards’ decided to reveal their existence and address, and the census sheets from some tenements in the ghetto did not reach the Jewish Population Registration Office at all – the authors calculated they had not received data from thirty-five (out of 295) houses assigned as blocks of flats for the Jews remaining in the ghetto, including the tenements that held about a thousand Werterfassungstelle employees, as well as an unknown number of ‘wild cards’. As a result, the census only covered 32,340 of the Jews legally residing in Warsaw, i.e. it omitted around 2,500 people. In the sample of the residential block of the Jewish Council and the Jewish Order Service the authors examined, 898 ‘wild cards’ were found among the 4,178 people listed (i.e. they constituted 21.5% of the total there), which is a lower estimate of the percentage of ‘wild cards’.

If we assume that in other parts of the ghetto the percentage of those unregistered was similar, then it is possible, using the official figure of 34,969 people living in the district officially, to estimate the number of ‘wild cards’ at around 7,500 and the total population at a minimum of 42,500. The authors of The Liquidation made a similar deduction; in their opinion the population of the ghetto after the deportations was 45,000, which seems a very conservative estimate, since the tenements not allocated to any institution were inhabited almost exclusively by ‘wild ones’. Similar figures were given by Abraham Lewin, who claimed that around 50,000 people remained in the ghetto in the final days of the deportations, from whom we must subtract a group deported in the last transport to the Treblinka extermination camp and several groups sent to labour camps. In the autumn of 1942, Emanuel Ringelblum presented a popular hypothesis in the ghetto: ‘some estimate the number of illegals at 7,000, others at 10,000 or even 15,000’. This would mean a maximum population estimate of around 50,000. The figure of 15,000 ‘wild cards’ was also postulated by the Demographic Note found in the Ringelblum Archives. In contrast, many diarists insisted on a higher estimate. The usually well-informed employee of the Labour Department, Stefan Szpigielman, believed that fifty-odd thousand people survived the operation, while Henryk Bryskier believed it was 55–60,000. These higher estimates coincide with the findings of post-war researchers. Berenstein and Rutkowski believed that there were 60,000 Jews in the ghetto in the autumn of 1942, and Engelking and Leociak agreed, while Gutman estimated the number of ‘wild cards’ to be at least 20,000, giving a total population of close to 55,000.

The ghetto population after the end of the deportation was therefore around 45–60,000 people – with the higher figure seeming closer to the truth.

During the ghetto deportations, the following died and were buried in the Jewish cemetery: 1,620 people on 22–31 July, 4,516 in August and 4,244 in September, including 3,767 by the middle of the month. These should be considered the minimum probable figures, as in the chaos of the extermination operation we may expected that many deaths (and executions) were recorded late or not at all. A significant proportion of the total buried died as a result of gunshots (30.7% in the last ten days of July, 51% in August and 74.1% in September), illustrating the increasing brutality of the blockades. The accuracy of the figures of those shot was debated in the ghetto. Abraham Lewin commented in late August 1942: ‘Some believe, e.g. Dr. R[ingelblum], that 15,000 people were killed, others maintain (police chief Brz[eziński]) that the number killed is “only” 6,000’. Brz[eziński]’s number corresponds to the burials that had taken place by the end of August, indicating he was presenting official data. It is difficult to determine where Ringelblum got his data from at this time. In his notes, he cites 12,000 killed during the operation – but it is not clear whether he was including those who died a natural death or only those who were murdered. It seems, however, that Ringelblum’s observation that the official statistics fell short was unwarranted. For example, he noted that 120 people were shot on 26 July, while no figures were recorded for that day.

During the same period, according to The Liquidation of Jewish Warsaw, 11,580 people were sent from the Warsaw Ghetto to a transit camp (‘Dulag’). This figure may be slightly low if we abide by information about small blockades on days when trains were not sent from Warsaw to Treblinka. For example: On 28 and 29 August, groups of returning workers were to be led to the Umschlagplatz, on 29 August several hundred workers from the Brauer plant, and on the following days groups of several dozen workers from other plants. It is possible that the Jews captured at that time remained imprisoned at the Umschlagplatz for a few days, until deportations to the death camp resumed, but it is also likely they were sent to the labour camps on an ongoing basis.

It is difficult to determine the number of Jews who escaped from the ghetto during the deportation period. Although sources agree that the first large wave of escapes to the ‘Aryan side’ took place during the deportations, a precise estimate of the number of escapees is impossible. A memo from the Underground Ghetto Archive estimates that 15,000 people escaped over the walls during the deportations, and several thousand more in subsequent waves. This figure is almost certainly exaggerated, although it also appears in the literature. Emanuel Ringelblum wrote in the autumn of 1942: ‘How many hid on that side? More than ten thousand’; yet he pointed out that a certain number later returned to the ghetto. Interestingly, Gunnar Paulsson, usually accused of overestimating, believed that around 6,000 escapees fled the ghetto during this period. For the purposes of the count below, we have used an estimate of 5–10,000 fugitives during the period in question.

The estimates are summarised below. As only the lower figures are estimates for the number of those who died in the ghetto and sent to the ‘Dulag’, the result should be regarded as a maximum estimate of deportees, and further research will probably allow us to narrow down the range.

Of the 353,000 Jews living in the ghetto on 21 July 1942, over the course of the following two months:

- Sent to labour camps (via ‘Dulag’) – at least 11,580 people

- Died in the ghetto – at least 10,380 people

- Fled the district – 5–10,000 people

- Remained in the ghetto – 45–60,000 people

- All others were deported to the Treblinka extermination camp.

The number of deportees estimated using this method is between 261,000 and 281,000.

Conclusion

The above estimates do not provide a precise determination of the number of deported Jews – the minimum estimate is separate from the maximum of 36,000 people. In order to narrow down this range, new sources or use new research methods are required. Personally, I am in favour of an estimate of 260–270,000 deportees, which is within the range of the estimate based on demographic data. This would mean that, following the intuition of the authors of The Liquidation of Jewish Warsaw, the ‘loaders’ underestimated the number of people packed into the wagons. However, lower estimates, which more closely match the daily records of deportees, cannot be dismissed out of hand. In order for them to be true, however, we would need to lower the estimated number of ghetto inhabitants before the deportations, thus undermining the results of the census of early 1942 and the subsequent data on the distribution of rationing cards.

Bibliography

- Arad Yitzhak, The operation Reinhard death camps, second ed., Bloomington 2018.

- Archiwum Ringelbluma, Podziemne Archiwum Getta, vol. 11.

- Archiwum Ringelbluma, Podziemne Archiwum Getta, 23.

- Archiwum Ringelbluma, Podziemne Archiwum Getta, 29.

- Archiwum Ringelbluma, Podziemne Archiwum Getta, 33.

- Berenstein Tatiana, Rutkowski Adam, Liczba ludności żydowskiej i obszar przez nią zamieszkiwany w Warszawie w latach okupacji hitlerowskiej, „Biuletyn ŻIH” nr 26/1958, s. 73 i d.

- Brustin-Berenstein Tatiana, Deportacje i zagłada skupisk żydowskich w dystrykcie warszawskim, „Biuletyn ŻIH”, nr 3/1952, s. 83 i d.

- Bryskier Henryk, Żydzi pod swastyką, Warszawa 2021.

- Engelking Barbara, Leociak Jacek, Getto warszawskie. Przewodnik po nieistniejącym mieście, second ed,, Warszawa 2013.

- Gutman Izrael, Żydzi warszawscy 1939-1943, tłum. Z. Perelmuter, Warszawa 1993.

- Mark Bernard, Życie i zagłada getta warszawskiego, second ed., Warszawa 1959.

- Paulsson Gunnar, Utajone miasto, translated by E. Olender-Dmowska, Kraków 2007.

- Raporty Ludwiga Fischera, gubernatora dystryktu warszawskiego, ed. K. Dunin-Wąsowicz, Warszawa 1987.

- Reich-Ranicki Marceli, Moje życie, Warszawa 2000.

- Sakowska Ruta, Ludzie z dzielnicy zamkniętej, Warszawa 1975.

- Sereny Gitta, W stronę ciemności. Rozmowy z komendantem Treblinki, Warszawa 2002.

- Stroop Jürgen, Żydowska dzielnica mieszkaniowa już nie istnieje!, A. Żbikowski, Warszawa 2009.

- Szpigielman Stefan, Trzeci front. O walce wielkich Niemiec z Żydami Warszawy, M. Janczewska, Warszawa 2020.