Pesach of Warsaw Jews (1940–1942)

“Jews are now very pious. They observe all the ritual laws: they are stabbed and punched with holes like matzas, have as much bread as on Pesach; they are beaten like hoshanas, rattled like Haman; they are as green as esrogim and as thin as lulavim; they fast as if were Yom Kippur; they are burnt as if it were Chanuka, and their moods are as if it were the Ninth of Av” (Rabbi Shimon Huberband – Kiddush Hashem pg. 113)

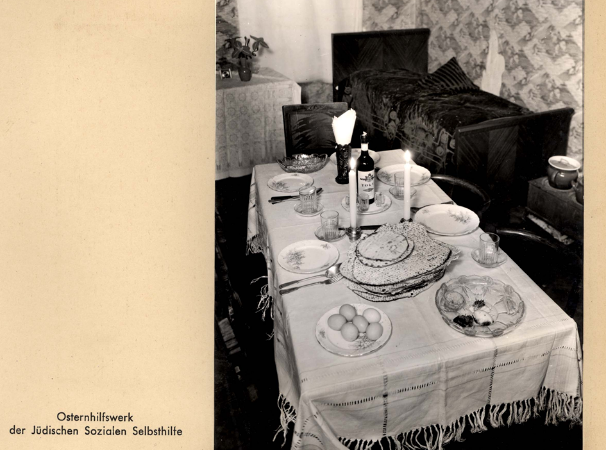

Seder dinner in a shelter for displaced persons at Leszno 6 St. (now Solidarności Avenue), 1940

“The synagogues are closed, but in every courtyard, there is a holiday service…without question even the poorest of the Jews does not lack for matza. On the eve of the holiday people ran around carrying packages of matza as though the sword of sabotage were not hovering over their heads. The whole thing seems somewhat unbelievable. Legally we have nothing to eat but the bread called for on our ration cards…Except for this allotment, one buys or sells bread at the risk of death…In every Jewish home the signs of the holiday are manifest…One factor which has not been mentioned helped greatly in the holiday preparation, and that is the Joint.”

Scroll of Agony – Chaim Kaplan (Indiana University press, 1999) pg.140

During the period from the German occupation of Warsaw in 1939 until the destruction of the Warsaw ghetto in 1943, the Pesach (Passover) holiday occurred four times. Even in normal times this major Jewish holiday requires a huge amount of preparation and organization in order to comply with the Jewish laws, and during the occupation this became increasingly difficult. Adam Czerniakow, in a diary entry dated March 20th 1940, states that “Permission was granted for the matzas for the Jews”. Similarly, in entries for the 4th and 7th of April 1940, he mentions difficulties with negotiations for obtaining the matza.

The specific obligation to eat the matza bread, especially on the first days at the traditional Seder meal, and the prohibition against eating regular bread, baked products and any foods produced with grain, caused huge difficulties and questions in a ghetto where starvation was rampant.

For the first Pesach, before the ghetto was sealed, the situation was somewhat better. In his diary from the Warsaw ghetto Chaim Kaplan describes the Pesach of 1940. He explains at length the confusion and crowding that occurred in the offices of the Joint before the holiday. He bitterly details the mismanagement and perceived corruption of the Warsaw representatives of the Joint Distribution Committee, repeating claims that seven and a half million zloty was allocated for support of the Jewish community during the Pesach holiday. It seems that the Joint elected to distribute food packages rather than financial aid, and that this process was mismanaged and that they failed to complete distribution by the eve of the holiday, finishing during the course of the holiday itself.

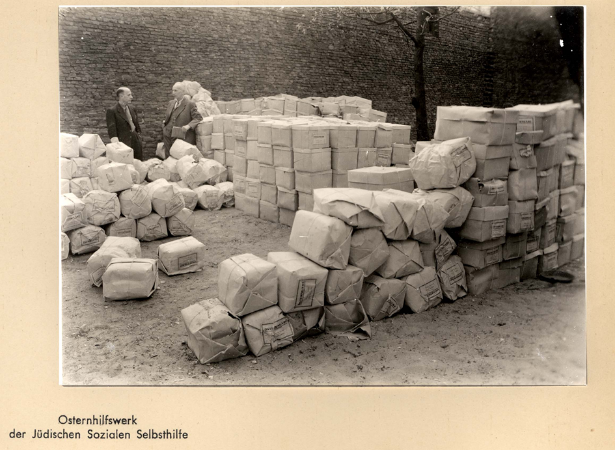

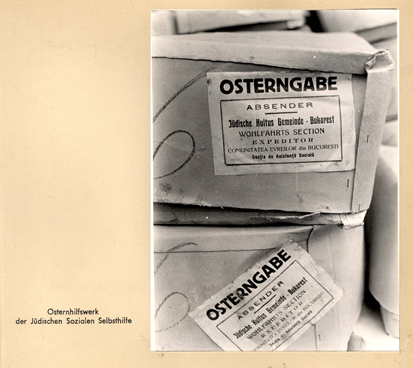

Due to a dispute over price, the “Joint” did not order matza from the Warsaw bakers choosing instead to buy from bakers in other towns and importing part of the supply from Rumania. A proportion of the flour and matza was subsequently confiscated in the towns and borders, and eventually much of the matza was only distributed during the holiday itself. This activity has been preserved for posterity in an album from the Jewish Self Help committee showing the various distributions, and the products including matza from Rumania.

Rabbi Shimon Huberband also describes the preparations for Pesach of 1940, “All winter long Jews worried about the problem of matza. During the week before Pesach, it became clear that although the Kehilla would not offer matza instead of bread for its ration cards, there would still be matza.

The rabbis permitted the use of flour already found in the market (normally unfit for baking matza). They made the bakers ovens kosher for Pesach, and matzas were baked. The price was steep, but the Joint Distribution Committee dispensed a huge amount of machine matzas which were shipped from abroad, and this kept the cost of matzas in check. The price of a kilo of matza was thirteen to fifteen zlotys. Some “shmura” matza, supervised from the time of reaping, was also baked from grain harvested during the summer of 1939 in the presence of Jews.

There were even matzas which were prepared on the eve of the festival, baked by a number of Chassidic rabbis for their own personal use. During the baking they sang (the psalms of) Hallel as in the good old days.

The peasants brought into town eggs, potatoes, and various vegetables. Everything was relatively expensive, but there were enough potatoes and vegetables to go around. The rich also had fish and meat for Pesach.

“The rabbis arranged contracts for the sale of chometz…There was an adequate supply of wine for the four cups, and the display-windows of various shops were filled with an assortment of wines…”

“An enormous campaign was carried out by the Joint, which distributed food packages consisting of matza, eggs, fat, sugar etc. In addition, the Joint distributed huge sums of money. The co-ordinating committee (later renamed the Jewish Social Self-Help Organization) also conducted a large aid campaign…”

“Despite the ban on public prayer, people assembled in all the courtyards in which several minyanim were held…Chassidim gathered together after the festival meals to drink liquor. They also did some singing, but softly. There was no dancing…”

Kiddush Hashem pg. 58

The fact that only the rich could have meat may have been partly due to the fact that according to Rabbi Huberband’s testimony, for Pesach of 1940, virtually no ritual slaughter of animals took place.

Kiddush Hashem pg. 220

By Pesach of 1941, the first Pesach in the ghetto, the situation had deteriorated dramatically. The starvation and poverty of the ghetto inhabitants is reflected in the questions of Jewish law put to various rabbis. Could one conduct the Traditional Seder meal without the four cups of wine, or matza? Was it permissible to use juice squeezed directly from grapes for the four cups? If a Jew hid bread before Pesach in order to eat it after Pesach, without selling it to a non-Jew for the duration of the festival, was it permitted?

According to Rabbi Huberband, both in 1940 and 1941, rabbis arranged the sale of chometz as they did before the war. In 1941, there was a serious problem of finding a non-Jew to whom to sell the chometz, due to the sealed ghetto although eventually a non-Jew was found and the chometz sold.

Kiddush Hashem pg. 205

On the last day of Pesach 1941, Rabbi Huberband was captured and sent to a forced labour camp.

Similarly, we find the comments of Chaim Kaplan reflect the changes. “Like the Egyptian Passover, the Passover of Germany will be celebrated for generations. The chaotic oppression of every day throughout this year of suffering will be reflected in the days of the coming holiday. Last year the Joint’s project was functioning full force. It was not conducted properly and many people criticized it, but in the last analysis it fed the hungry and bought the holiday into every Jewish home. We lacked for nothing then.

This year everything has changed for the worse, and we are all faced with a Passover of hunger and poverty, without even the bread of poverty (a reference to matza). First of all, the Joint has divested itself of all activity in connection with the holiday…As the holiday drew near, the Self-Aid made the customary Passover appeal for money for the poor. But this project was born in an unlucky hour and its results will be nil. At present, one week before the holiday, the projects treasury is empty. What then will we eat during the eight days of the coming holiday? For prayer there are no synagogues or houses of study…For eating and drinking there is neither matza or wine.”

Scroll of Agony – Chaim Kaplan (Indiana University press, 1999) pg. 262

David Berman – Talmudic scholar, researcher of Jewish texts. Born in Sydney, Australia. Studied in Gateshead Yeshiva in the United Kingdom where he obtained his rabbinical ordination. After relocating to Israel, he lectured and continued his studies of Jewish law and classical Hebrew works in various institutions specialising in in-depth analysis of halacha, among them the Tzanz Talmudic Academy. He resides in Warsaw.