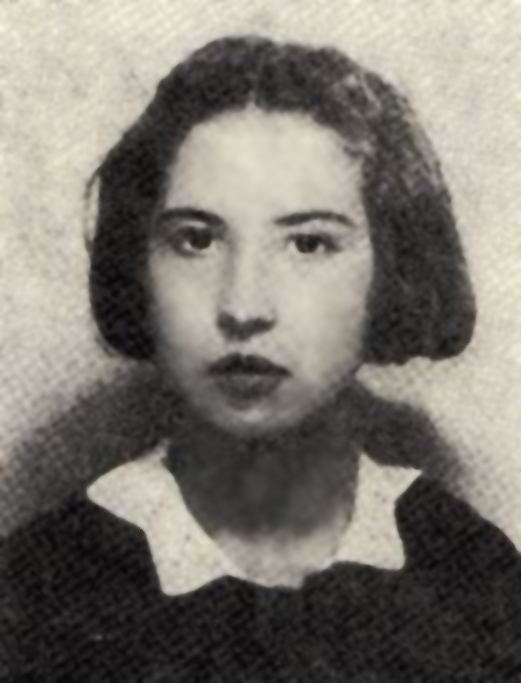

Mira Fuchrer (1920–1943)

Leader of the Ha-Shomer ha-Tzair movement, member of the Jewish Combat Organization (ŻOB), and heroine of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising.

She was born in Warsaw in 1920. There were rumors that her father was a staunch communist who fled to the Soviet Union due to persecution by the Polish authorities and subsequently disappeared. At that time, Mira was still a young girl. She lived with her mother and sister in modest conditions. Mira’s older sister, Tamar, introduced her to the left-wing Zionist youth organization Ha-Shomer ha-Tzair (Hebrew: The Young Guard). In 1938, Szmuel Breslaw—the leader of the Ha-Shomer battalion “Maanit”—asked Mira to take over his position while he went away to a training camp. Mira began to frequent the Warsaw branch headquarters of Ha-Shomer, where she met Mordechai Anielewicz, who would later become her life partner.

Mira Fuchrer | Public Domain

Just after the outbreak of World War II, together with other Ha-Shomer leaders, Mira traveled to Vilnius, seeking a way to reach Palestine. However, in January 1940, she returned to Warsaw with Anielewicz. From November of the same year, she was confined to the Warsaw Ghetto. Historian Israel Gutman, who personally knew Mira and Mordechai in Ha-Shomer ha-Tzair, cites a letter from Mira to a friend living in Vilnius, written in 1941, in his book ”Mered ha-netsurim” (“The Revolt of the Besieged”). In the letter, Mira confides that both she and Mordechai were very busy with organizational matters, and that she was happy and deeply in love with Anielewicz.

“People always saw Mira in a whirlwind of action. Her hands, feet, and face were always in motion. But if one looked closer, one could see an expression of happiness in her eyes, which stayed with her until the end.” [Gutman]

In the ghetto, Mira worked in a small tailoring cooperative with Towa Frenkel and Rachela Zylberberg. She was also a member of Ha-Shomer’s central command.

Between mid-1941 and the summer of 1942, together with Anielewicz, Szmuel Breslaw, and Towa Frenkel, she operated a clandestine radio monitoring station. Notes from the broadcasts received from abroad were published as bulletins and used by the editors of other underground papers. This way, ghetto inhabitants—cut off from the outside world—could learn what was happening beyond its walls. For most of that time, the station operated from a covert apartment at 11 Pawia Street. Mira lived there for about a year. Her fellow Ha-Shomer members would come to the apartment to monitor and transcribe the broadcasts—also at night. This situation exposed Mira to risk, as neighbors and building staff looked suspiciously at the nightly visits of two men. In September 1941, she was summoned by the building’s administrator and accused of immoral behavior—the matter was resolved with a bribe. Mira also distributed illegal press throughout the ghetto.

Aliza Witis-Shomron, who joined Ha-Shomer in the ghetto as a teenager and was a member of the girls’ group “Avukot,” recalls Mira in her memoir “Neurim ba-esh”:

“We also adored Mira Fuchrer. There was an aura of mystery about her. We knew she was Mordechai Anielewicz’s girlfriend. There were even rumors that they lived together on Leszno Street. Mira was a short brunette, with cropped hair and full lips, and always had a hoarse voice. Her high cheekbones gave her a slightly Asian look. She was usually serious, but she had a wonderful smile and loved to laugh. She often sat among us, listening in silence, but when she spoke, she did so clearly and decisively. We listened to her intently. In winter she wore a short sheepskin coat, tall boots—which were fashionable at the time—and a navy blue beret. That’s how I imagined people from Narodnaya Volya, the young Russian revolutionaries…”

Witis-Shomron also recalls Mira’s speech to members of the Ha-Shomer cell during a secret meeting on April 18, 1942—the morning after the so-called “Bloody Friday”, when the Germans killed 53 individuals connected to the ghetto underground. Members of the movement sat silently on the floor, devastated by the events of the night, when Mira spoke:

“Now we are entering a turning point in our lives that will force us to separate and dissolve our unit. We must prepare for a painful farewell. The situation demands it. Remember, our goal is always—until the last moment—to remain true to the ideals of the Shomer and of humanity. […] We will not abandon the principles that shaped us. We will continue to strive toward our ideals as free people. We will not surrender and will not bow before the enemy who seeks our annihilation.”

After the establishment of the Jewish Combat Organization (ŻOB) in the summer of 1942, Mira immediately began working as a liaison for the command. As part of this role, she also traveled to other ghettos in occupied Poland. During these missions, she left the ghetto in disguise. Witis-Shomron further recalls in her memoir meeting Mira in the fall of 1942—between deportations—at the organization’s headquarters, from where couriers were dispatched:

“She was hard to recognize. She wore a blue hat with a wide brim that partly covered her face. Her hair was styled in curls then fashionable among Polish village girls. She was dressed and made up like a young Polish woman on her way to a date. Who would have recognized the modest and ascetic Mira from a few months earlier! She told us how she crossed over to the Aryan side through a cemetery, where she met Polish couriers who supported us. Her voice was as hoarse as ever, but there was a sparkle in her eyes, like someone fulfilling her dreams.”

In February 1943, Mira, along with other fighters, participated in a raid on the Judenrat treasury. The operation was successful—Mira and Towa Altman transported the 100,000 zlotys they had obtained in a food kettle to ŻOB headquarters.

Aliza Witis-Shomron, who survived the war and later settled in Israel, gave an interview on April 22, 2025, during her visit to Poland, to the Warsaw Ghetto Museum and the Jewish Historical Institute[1]. In it, she described how Mira organized meetings of Ha-Shomer members in 1943, while Mordechai Anielewicz was in hiding to avoid arrest by the ghetto police. She recalled:

“Mira was very kind, but also firm. She convinced people to donate money for the purchase of weapons for the ŻOB.”

During the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, which began on April 19, 1943, Mira fought in the central ghetto alongside Mordechai Anielewicz. The initial resistance of the Jewish fighters completely surprised the Germans, who were twice forced to retreat from the ghetto in the first days of fighting. After several days, the situation for the fighters became increasingly dire. The ŻOB command, including Mira, moved to a bunker at 18 Miła Street. They stayed there for some time. On May 8, the Germans located the bunker, surrounded it, and released gas inside. Most civilians exited and surrendered to the Germans. However, about 120 ŻOB fighters chose not to surrender. They remained in the bunker and died there.

According to some reports, Mira and Anielewicz committed suicide, though—as Hela Ruffeisen wrote after speaking with Tosia Altman, who escaped the bunker—Anielewicz opposed this decision:

“He believed that placing a wet cloth over one’s face could protect against the gas. This was how Mordechai, Mira, and others tried to save the fighters nearby.”

By the decision of President Bolesław Bierut, on April 19, 1948, Mira was posthumously awarded the Silver Cross of the Order of Virtuti Militari. The citation reads:

“For merit in underground combat during the occupation. Member of the ŻOB. Comrade-in-arms of Mordechai Anielewicz, distinguished by exceptional bravery. Died in the ŻOB command bunker on Miła Street.”

Bibliography:

- Ringelblum Archive, vol. 22: Warsaw Ghetto Press: Radio Interview News, Warsaw 2016.

- Bernard Mark, “The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising”, Warsaw 1963.

- Gutman Israel, “The Jews of Warsaw 1939-1943”, Warsaw 1993.

- Gutman Israel, “Mered hanetsurim: Mordehai Anilevits wemilhemet geto warsza”, Jerusalem 2013.

- Rufeisen-Schupper Helena, “Farewell to Miła 18:”, Cracow, 1996.

- Witis-Szomron Aliza, “Młodość w Płomieniach” („Neurim ba-esh”) Warsaw 2013.

- Zawadzka Elżbieta (ed.): “Biographical Dictionary of Women Awarded with the Military Order of Virtuti Military”, Toruń 2004.

[1] Interview conducted by Masza Makarowa (Warsaw Ghetto Museum) and Maria Ferenc (Jewish Historical Institute) on April 22, 2025 in Kraków.