WGM Collection: ‘Mechitza’, Zuzanna Hertzberg

‘Daughter of Anna, granddaughter of Krystyna and Janina’. This is how Zuzanna Hertzberg, an artist whose banners from the Mechitza series are part of the Warsaw Ghetto Museum collection, begins her biography. Their protagonists are Jewish women who fought against the Nazis in various ghettos in occupied Poland, not just during the largest armed outbreak, the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising.

Hertzberg reaches back into history, restoring female fighters to their due place, describing their herstories. When feminist scholars coined the term herstory in the 1970s as a counterbalance to the male perspective on history (his-tory), they were demanding women be restored to their proper place in historical narratives and reference be made to their experiences. For contemporary female scholars and authors, herstory is not only a polemical stance against the male ‘writing’ of history, but a conscious look at history from a female perspective. This is Hertzberg’s point of view, as well.

Zuzanna Hertzberg (b. 1981) studied painting at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, where she received her doctorate in art in 2018. She is an interdisciplinary artist whose work combines traditional media (such as painting, assemblage, object or fabric) with performance and social activism. Her creative stance is best described as artivism, i.e. a conscious combination of artistic practices and an activist stance. Through her art, she fights discrimination and advocates for marginalised groups, speaking up for the rights of minorities and women. In this context, her complex Polish and Jewish identity is of great significance. Hertzberg’s interest in history, in researching archives, in memory (including historical memory), but also in the political dimension of artistic gestures, stems directly from her roots. At the same time, her activities are embedded in the present, and, despite their historical background, are thoroughly topical. Hertzberg has developed the idea of nomadic memory; a good example of an action that incorporates history and contemporary life is The Dąbrowszczaks – The Cursed among the Cursed of 1 March 2016. In the introduction to her book Kwestia charakteru. Bojowniczki z getta warszawskiego (A Question of Character: Female Fighters from the Warsaw Ghetto), she writes of it as follows: ‘For the purposes of my activist art strategies, I have coined the notion of nomadic memory, memory as a rhizome – wandering, undomesticated, cross-border, transnational, revived in many places and times, equally “remembering” and prompting reflection on the present. And, most importantly, calling us to action today. For the people who hold on to it, it is not a just stock of documents, but an active mechanism, a field of forces. My first application of this notion took on the erased memory of the Dąbrowszczaks, volunteers of the International Brigades, which I moved into the public space. Taking over the key founding myth of the Cursed Soldiers from the nationalist narrative, I queered it, introducing the sociopolitical category of the Cursed among the Cursed. In this way, I tried to show the political mechanism of erasing inconvenient threads of our history.’

Hertzberg has explored the topic of Jewish women’s participation in anti-fascist movements since 2016. In objects from the Volunteers of Freedom (2016–20) series, she profiled women who fought General Franco’s fascists in the Spanish Civil War (1936–39). The works were accompanied by spoken performances, which were the artist’s stories about her heroines. The same structure – object and performative commentary – was used for the Mechitza project, ongoing since 2019, in which Zuzanna Hertzberg has evoked the memory of Jewish women who fought during the Second World War in the ghetto and beyond the wall, on the ‘Aryan side’. The mechitza of the title, a partition in Orthodox synagogues separating women from men, plays a symbolic role here. It could be a wall, a screen or a curtain dividing the two prayer spaces. In the context of the artist’s chosen theme, the mechitza signifies, on the one hand, the separation and marginalisation of women, and on the other, a break with the prevailing narrative and the restoration of the historical memory of Jewish women fighters.

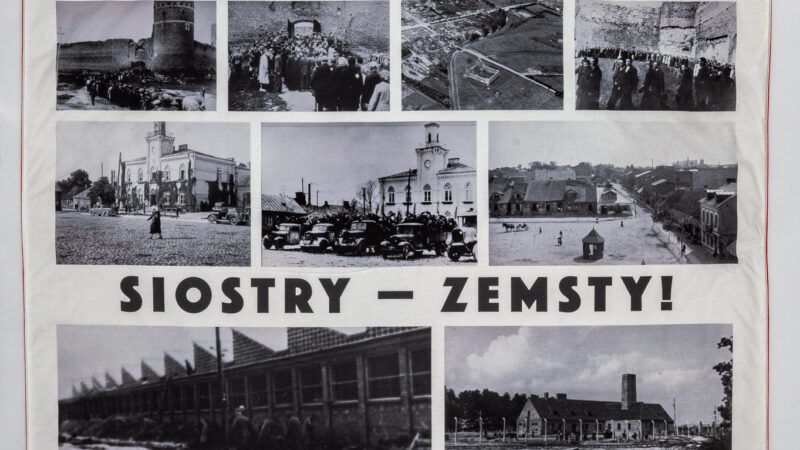

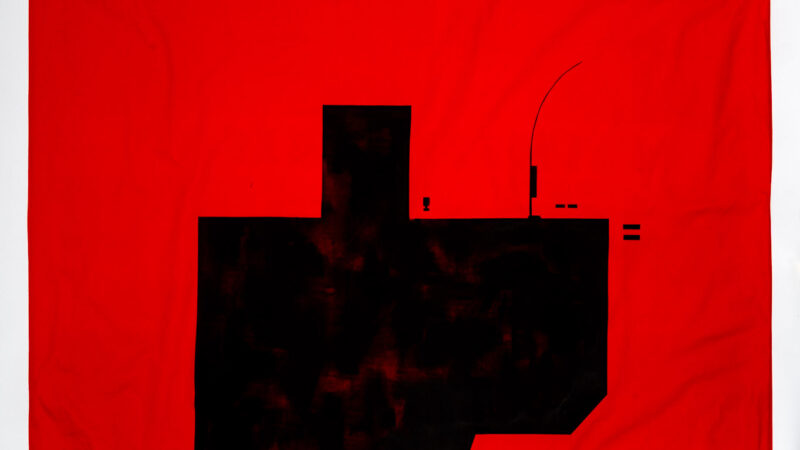

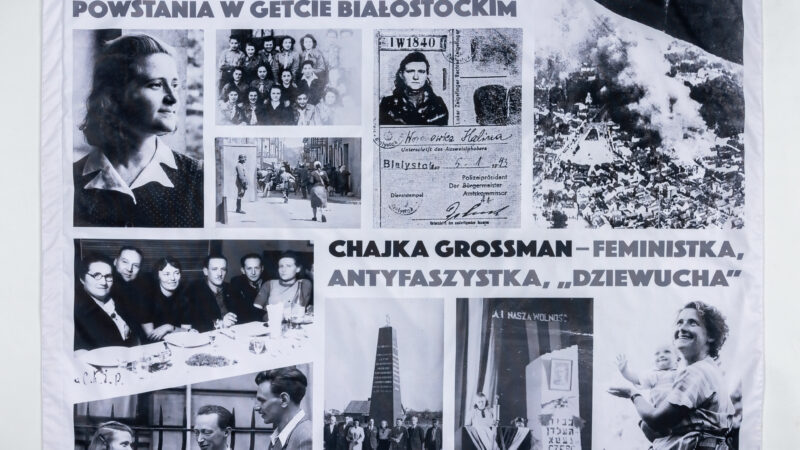

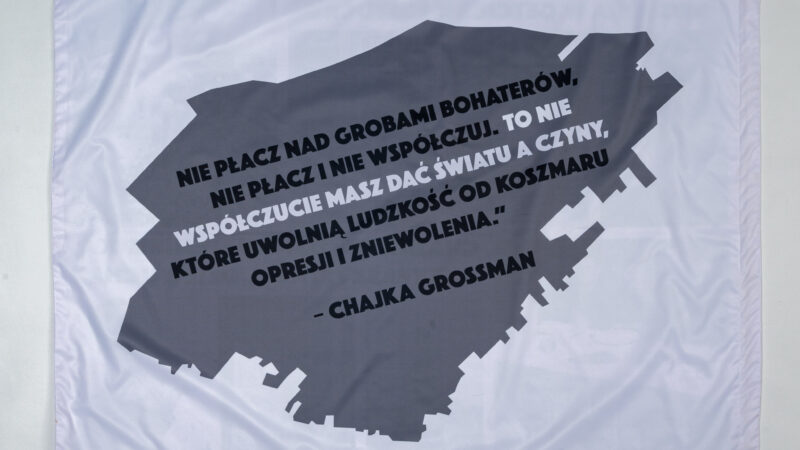

The objects created in this series, part of the MGW collection, are fabric banners presenting selected heroines of the Jewish resistance. Collages of archival photographs and materials have been printed on the textiles; on their reverses, most of them have maps of places where acts of resistance and combat took place. All of the canvases have looped ends for their display in a gallery or museum, but also put on trees and shown in much more dynamic situations – on the street, in action. The oldest part of the project, Mechitza: Women’s Individual and Collective Resistance during the Holocaust, consists of three banners with photographs of women fighters and archival documents. The banners are accompanied by commentary slogans: ‘Sisters – Revenge!’, ‘You will survive – you will tell our story’ and ‘Yes, it’s true, I organised groups of Jewish fighters and I promise that if I get out of here, I will continue’. The back of each cloth, with a drawing of a map, is a different colour: blue, yellow or red. Another banner – Mechitza: Female Fighters of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprisings – features archival portrait photographs of six women, signed with their first and last names: Niuta Tajtelbaum, Cywia Lubetkin, Tosia Altman, Regina Fudem, Guta Kawenoki and Fela Talman. The reverse is analogous. The third work, Mechitza: Chajka Grossman, is a collage dedicated to the organiser and fighter of the Bialystok Ghetto Uprising. ‘Chajka Grossman – feminist, anti-fascist, “ninny”,’ proclaims the text between the photographs. The artist has inscribed a quote from Chajka Grossman on the back, in the shape of a map of the ghetto: ‘Do not weep over the graves of heroes. Do not weep and do not feel sorry. It is not compassion you must give to the world, but actions to free humanity from the nightmare of oppression and enslavement.’ Hertzberg first showed this work during an action in a public space on the 77th anniversary of the Bialystok Ghetto Uprising.

Who were these heroines of Zuzanna Hertzberg’s Mechitza? They were all active in society even before the war; most of them belonged to the Jewish Combat Organisation in the Warsaw Ghetto, although there were also members of the Anti-Fascist Bloc. Most of them died in 1943 or 1944. Cywia Lubetkin and Chajka Grossman survived the war. The former fought in the Warsaw Uprising, was active in the Bricha Zionist organisation after 1945, and emigrated to Palestine in 1946. In 1961, Cywia Lubetkin testified in the trial of Adolf Eichmann. She died seventeen years later. Chajka Grossman was active as a liaison officer between ghettos in Poland, Lithuania and Belarus from 1941 onward. After fighting in the Bialystok ghetto, she made her way to the ‘Aryan side’. She worked, fought in the partisans, and after the liberation, was active in the Zionist movement. She emigrated to Israel in 1948. Between 1969 and 1988 (with a brief interruption), she was a member of the Knesset for the left-wing Mapam party. She died in 1996.

A symbolically important figure for the artist is the mythical Lilith, who appears in the commentaries on the Mechitza series. In the opening essay of the collection A Question of Character, Zuzanna Hertzberg recalls the moving story of Regina Fudem: ‘Many Jewish girls of the Holocaust era carried that Lilith within them, erased from the canonical scriptures in the name of religious propriety decreed by the guardians of male morality. One of them, Regina Fudem, even used it as a pseudonym. Ignoring the men’s orders, she put a revolver to her temple as a threat and a refusal, so that she could return through the sewers to the burning ghetto to fetch her comrades. She wanted to decide for herself, and she paid the ultimate price for this act of solidarity and radical empathy. She died in battle’.

Zuzanna Hertzberg’s project restores the memory of women fighters, but also points out that their heroism did not eliminate their feelings; they were heroines denied the right to emotion, error, ‘weakness’. The artist writes: ‘The paradigm of male heroism excluded what we all know today – that what is private and intimate also becomes political in borderline situations, and that the body, as we also know, is a battlefield. It is a risk a woman bears to a much greater extent than a man in this struggle’. By adopting a herstorical perspective, Susanna Hertzberg emphasises her female point of view. She also consciously chooses fabric as the material for these works – not only to refer to the curtain separating the world of men and women in the synagogue, but also because fabric is commonly perceived as a feminine medium. Empathy, emotionality and delicacy do not preclude strength and heroism. Hertzberg, a contemporary artist/activist taking her art to the street, recognises this formative role of women from the past; she sees a continuity. In macro and micro history. Daughter of Anna, granddaughter of Krystyna and Janina.

Marta Miś – art historian, film scholar, curator, editor. Between 2011-2022 she worked at the Zachęta National Gallery of Art, where she curated, among others, the exhibitions Jacek Malinowski. Bipolar, Aleksandra Kubiak. Śliczna jesteś Laleczko, Mariusz Wilczyński. Kill it… Author of essays on cinema and visual arts. She has published, for example, in the monthly magazine ‘Kino’, the catalogues of the New Horizons IFF, and exhibition catalogues. Since 2022, she has been associated with the Gallery of Contemporary Art in Opole.