January Self-defence 1943

Perhaps, had it not been for the January Uprising, the April Uprising in the Warsaw Ghetto would not have taken place. Read more about the first self-defense action in the Warsaw Ghetto.

The Warsaw Ghetto, from the moment it was established by the German occupation authorities on 2 October 1940, closed and isolated from the rest of the city on 16 November 1940, functioned as the so-called “Jewish Quarter”. In the summer of 1942, the Germans began the first stage of its liquidation (the so-called Great Action carried out as part of the Operation Reinhardt). The actions were preceded by terror and propaganda, the purpose of which was to persuade the ghetto prisoners to voluntarily “resettle to the East”.

In fact, from 22 July to 21 September 1942, the goal was to kill as many Warsaw Jews as possible in the Treblinka extermination camp. At that time, the majority of ghetto activists – social activists and members of political groups in opposition to the Judenrat – rejected the idea of armed resistance as they did not want the remaining population to be annihilated. Fear, an awareness of one’s own weakness in the face of the criminal German machine and lack of faith in the sense of taking up the fight prevailed.

As the Jewish community in Warsaw continued to shrink, those who survived received more and more information about the progressing Holocaust. Nearly 270,000 Jews died in the ghetto, on the way there and in Treblinka, while approximately 65,000 to 70,000 survived the action and remained in the “closed quarter”. Few of those recieved life-saving numbers: stamped and signed yellow pieces of paper allowing a temporary stay in the “residual ghetto” and obliging to work in the shops (self-sufficient German enterprises, closed enclaves within the ghetto). Others, so-called “wild” Jews, had to hide.

In September 1942, when the first stage of the ghetto liquidation was coming to an end, many survivors re-evaluated their views. They also felt guilty for their passive attitude during the period of forced “resettlement”. This could be noticed in the words of the ghetto chronicler, Emanuel Ringelblum, who wrote at the end of 1942:

If men, women and children, young and old, had opposed, there would not have been 350,000 murdered in Treblinka but only 50,000 shot in the streets of the capital city.

The majority, both “registered” as well as “illegal”, were young, precocious, aware of the fate of their relatives, friends and strangers that might have been their fate soon, too. In such extreme conditions, aware that they had nothing left to lose, they decided to resist and turn their previous helplessness into sacrifice. Izrael Wilner, the representative of the Jewish Combat Organisation (ŻOB), put it that way:

We do not want to save our lives. None of us will get out from here alive. We want to save human dignity.

It was them – the members of left-wing and Jewish youth groups – who at the end of July 1942 started the resistance movement: the Jewish Combat Organisation. At the turn of 1942/1943, right-wing Jews established the Jewish Military Union (ŻZW). The main goal of the underground Jewish organisations was self-defense. They lacked weapons, however they were highly determined. They established cooperation with Polish underground. Weapons were purchased on the “Aryan” side, depending on the possibilities and financial resources. Grenades, mines, powder bulbs and Molotov cocktails were manufactured in the ghetto.

In addition to the preparations for self-defence, in January 1943, ŻOB planned to carry out a protest action under the slogan:

Honour the fallen – on the occasion of the first half of the extermination period, 22 July 1942 – 22 January 1943.

The action was supposed to take place in the afternoon. The fence of the Muranow Square had to be decorated with wreaths and banners. Indirectly, such actions were to be evidence of the changes that had taken place in the Jewish environment over the course of several months: the ŻOB fighting units were to demonstrate their ability to act and to use force against the Jewish Order Service in accordance with the order of their commanders. The ŻOB fighters, however, failed to implement their plans. The Germans who intended to carry out the second stage of the liquidation – deportation of 16,000 Jews to Treblinka within the next few days – were faster.

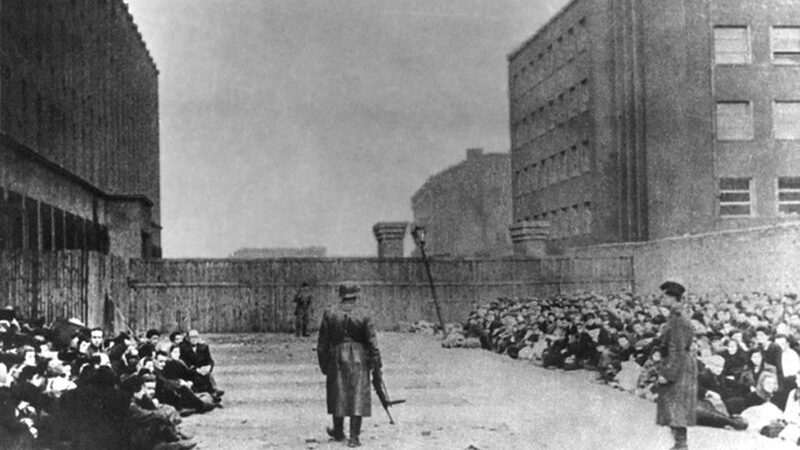

The confrontation of the unequal forces took place in the early hours of Monday morning, 18 January 1943. It was a total surprise for the ghetto underground. The lack of communication, and thus the inability to carry out any coordinated action against the Germans, was apparent. The management of the shops was ordered to tell all workers to go to the Umschlagplatz. The effects were negligible, so the Germans (with the support of Ukrainian and Lithuanian troops) initiated round-ups. The “life-saving numbers” were no longer taken into account. What mattered was the number of nameless people assigned to be put to death. The victims of the “round-ups” tried to resist at least in a symbolic way – like the Bund members who, led to the Umschlagplatz, were killed for refusing to enter the cattle wagons. Many decided to resist actively, following the ŻOB leaflet which was circulated on 18 January. It read:

Jews! The occupier proceeds to the second act of your annihilation! Do not let them keel you freely! Fight! Grab an axe, crowbar or knife, barricade your houses! Let them struggle to get you! The fight is your opportunity to save yourself… Fight….

Many young Jews took those words literally. They didn’t want to act in a different way. One of them was Yasha Grynsztejn, who, with a knife in her hand, attacked an SS-man and died. Another one was Mordechai Anielewicz, who, with a group of fighters, tried to save people led to the Umschlagplatz. Most of the fighters were killed. Dozens of convicts managed to escape, instead. Anielewicz survived…

However the fact that ŻOB and ŻZW fighters managed to overcome their fear was the most important. Danny Falkner, one of the fighters, said: “I felt euphoria after the first Jewish shots, we saw that the Germans were not immune to violence”. In turn, Cywia Lubetkin noticed:

The Germans (…) lost control of the situation. We could hear them shouting: “The Jews are shooting at us!”

It was a different type of fight – urban guerrilla: small, poorly armed units took advantage of the conditions in the ghetto. Jews rarely decided to confront the forces in the streets, they defended buildings instead, attacked the enemy in the shops, set fire to German warehouses, and punished those suspected of treason. The fights weakened on 20 January. German troops no longer entered buildings or shops. In fact, they limited their actions to round-ups. They left the ghetto two days later.

The self-defense delayed the liquidation of the Warsaw Ghetto, and the Jews who survived could build their fighting ability. The ŻOB message of 27 January emphasised that fighting was the only alternative:

There is little hope that we can escape so let’s act on the spot. Every house should be a fortress.

The ghetto prisoners started building bunkers, hidden passages between buildings and tunnels leading to the “Aryan” side. They started collecting food, too. A hidden, underground city was founded. “The January experience” forced the Jewish resistance movement to reinforce its ranks, to concentrate and keep the fighters in the kibbutzim, in strategic locations, to remain vigilant and ready for immediate action in case of danger. More importantly; however, Jews no longer felt like powerless victims. Their role changed:

It’s different today” – said Hersz Berlinski – “Now, the Germans have to conquer the ghetto.

Perhaps, had it not been for the January Uprising, the April Uprising in the Warsaw Ghetto would not have taken place.

On 18 January 1943, there were several hundred members of ŻOB, forming approximately 50 fighting units. Five of them survived by 22 January. Almost 1,200 Jews died in the ghetto – in the streets, in the buildings, in the attics and cellars, in the hospital, in the shops and on the Umschlagplatz. Approximately 5,000 were deported to Treblinka. Twelve Germans were killed, dozens were wounded: the life of a German was precious, the heroism of Jews was priceless…